Emancipating the Bell Family: An Inquiry into the Strategies of Freedom-Making

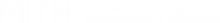

On the evening of Friday, April 21, 1848, a large crowd gathered at a railroad depot within view of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. There were tears of farewell not unusual in the setting of so many partings. But unlike the typical leave-taking of friends and families at the end of a journey or the start of one, those present at the depot that evening were not there to wish their loved ones safe travels, but to bid them farewell, without any certainty that they would ever be reunited again. Rough-looking men stood guard with canes in their hands, ready and willing, maybe even eager, to put rod to flesh to maintain order and keep the tearful crowd away from the occupants of a train car. This was no ordinary railcar, but a make-shift prison housing fifty enslaved men, women, and children who were soon to be sent to Baltimore and from there, sold into the deep South. Just days earlier, most had very nearly gained their freedom aboard a schooner called the Pearl, only to be captured less than two days into their escape.

"First Railroad into Washington and Its Three Depots," Records of the Columbia Historical Society 27 (1925): 179.

A middle-aged man named Daniel Bell stepped out from the crowd and approached the car, pleading with the slave dealer to let him see his wife, Mary, one of the fugitives from the Pearl. She was free, he explained. She even had the freedom papers to prove it. His protest fell on deaf ears. As he drew near to one of the car windows where his wife was standing with her hand outstretched, the slave trader knocked him away.1 The train eventually pulled out of the station, but the Bell family's quest for freedom did not end there. In fact, it had begun much earlier, long before the attempted escape on the Pearl, and would continue through the American Civil War.

In all, the Bells brought seven different court cases in Washington, D.C., over the span of fifteen years, each one designed, like a ladder, to support a foothold for another step toward their family's total freedom. Some of the Bells secured their liberty. Eventually, however, the courts failed them, so Daniel and Mary turned to other means. Because of their involvement in one of the largest known bids for freedom in American history, the story of the Bells has previously only been told as it relates to the Pearl affair.2

The Bells' story uncovers a central truth of freedom-making: families bargained in private and used the public forum of the law interchangeably and in relation to one another in their pursuit of liberty. There was no one path to freedom.

The Pearl escape, though dramatic and highly consequential, was only one part of a much larger narrative of freedom-making, contained in a fragmentary historical record including court documents, wills and inventories, census pages, and Freedman's Bank accounts. Following this trail of evidence, the Bell family comes into sharper focus, and a detailed portrait of freedom-making comes into view. Even as some parts remain unknown, some identities unclear, and some connections and relationships undetermined, the Bells' story uncovers a central truth of freedom-making more broadly: families bargained in private and used the public forum of the law interchangeably and in relation to one another in their pursuit of liberty. There was no one path to freedom. This is one family's story of emancipation in the heart of the nation's capital.3

* * *

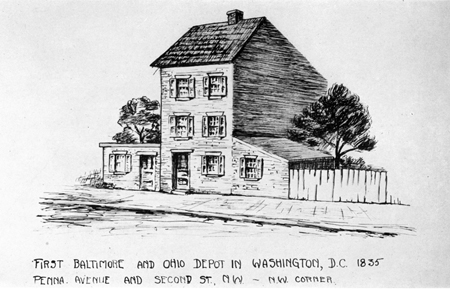

Two years after the turmoil of the Pearl incident, Daniel Bell and what remained of his family were residing on F Street in Southwest D.C., not far from the wharf where the ill-fated escape attempt departed from. In that same dwelling was a second family group, including Ann and Lucy Bell and a man named James Ash. Ann and Ash were no strangers to freedom-seeking either. Ten years earlier, Ann had filed a freedom suit in the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia. Although her petition was filed December 24, 1836, summons after summons was returned to the court marked "Non Est" by the marshal—non est inventus, not found. The defendant, Gerard Truman Greenfield, was not a resident of the District at all, but rather of Maury County, Tennessee. However, Greenfield was forced to keep his enslaved property in D.C. based upon the dictates of his inheritance.4

Three years after Ann filed her petition, while her summonses went unanswered, James Ash filed his petition in December 1839. He, too, had been claimed by Gerard T. Greenfield, who sold him to a slave dealer, contrary to specifications in the will of his aunt, from whom Gerard had received enslaved property, including Ann and Ash. The court found in favor of Ash's freedom, but the case was appealed to the Supreme Court, based on the argument that the restrictions in the will went against a slaveholder's right to property. The Supreme Court disagreed, stating that the conditional nature of the bequest of freedom was not inconsistent with the right to property. Ash was declared free by the Supreme Court in January 1843.5

But while Ash's case hinged on a question of law, Ann's case centered on a question of freedom. Although some of the specifics are difficult to piece together from the court records that remain, the point at issue in her case seems to have been whether or not she was freed by the 1815 will of Gerard's uncle, Gabriel P. T. Greenfield.6 Despite having gone about as a free woman for over a decade, Ann's liberty was in jeopardy and potential separation from her family imminent. The precariousness of freedom and the ease with which it could be stripped away was an ever-present reality of both free and enslaved families, a burden that the Bells carried during their many bids for freedom.

* * *

While many of the Bells eventually found their way to Washington, D.C., the family's roots extended back to Prince George's County, Maryland. Both Ann and Daniel Bell were the children of an enslaved woman named Lucy, who was born on the eve of the Revolutionary War.7 Little is known about her except for the names of her children and that by 1850, she had claimed her freedom and was living in the same house as Daniel, Ann, and James Ash. Prior to 1796, Lucy and an infant Ann were held as the property of Gerrard Truman Greenfield, the grandson of early Maryland settlers, Thomas Greenfield and Martha Truman.8 Upon the death of Gerrard in 1797, the Greenfields appear to have separated mother and daughter. Lucy was passed on to his widow, while young Ann became enslaved by one of the Greenfields' sons, Gabriel. Over the next 13 years, Lucy gave birth to at least four more children, whom Gerrard's widow, also named Ann, bequeathed to her own sons and daughters upon her death in 1810. Death in the Greenfield family meant separation and uprooting for the Bells. Daniel Bell would have experienced at an early age the loss of siblings and parents, the violence and terror of their separation, and the constant dread of an unexpected visitation from the eponymous Georgia slave trader.

Death in the slaveholding Greenfield family meant separation and disruption for the Bells, a cruel reality of slavery that Daniel Bell learned at an early age.

Of Lucy's children, Caroline was sent to Ann T. Beall, likely living in Washington, D.C.; Prisseller became enslaved by Maria Amne in Prince George's County; Daniel and Harriet were sent to Gabriel, also living in or a frequent visitor to the D.C. area, and who was already slaveholder of Ann by his father's will; and Lucy appears to have been sent to Walter in Prince George's County, her body a part of the remainder of his mother's estate. Later records relating to the Bells give no mention of a Prisseller or Priscilla, but there are two more siblings named Kitty or Cathie and Ellen Nora or Eleanor.9 Gabriel Greenfield's death in 1815 sent Harriet into the possession of his sister, Sabina, and Ann to Maria Amne. It is unclear what happened to Daniel, but like several of his siblings, he eventually found his way to Washington, D.C.

Ann Bell seems to have been the first in her family to arrive in the capital. According to the documents filed in her freedom petition, she came to reside in Washington in 1813 or 1814 with the permission of Gabriel Greenfield. In the years that followed, Ann continued to live in D.C., seemingly without interruption for at least twelve years. Then, in 1836, the slaveholding Greenfield family claimed she had been enslaved all along. Ann's sister, Caroline, also apparently conducted herself as a free person around this time, presumably in the District, and perhaps living with their mother. A freewoman named Lucy Bell appeared in the 1820 census. The household contained one male slave age 14-26, one female slave under 14, one free colored female under 14, and one free colored female age 26-45. It is possible that this was Lucy and some of her children, including Daniel. The household was living just north of the Navy Yard, near the same area of Washington that the Bells lived in from 1850 onward. Not far from the Bells was the George Blagden household. Blagden's son, Thomas, would become a key ally to Daniel as he negotiated his freedom and that of his family years later.10

The Bell Family's Washington, D.C., c. 1820-1880. View the Story Map.

Sometime during the 1820s, Daniel Bell began working in the blacksmiths' shop in the Navy Yard as a fireman, casting and molding ironworks. Perhaps here he first encountered Mary, a woman enslaved by Robert Armistead, who worked as a quarterman caulker and carpenter. Armistead (also frequently spelled Armstead) was born in York County, Virginia. It is unclear how he came to reside in the capital, though likely through his occupation. Despite being a slaveholder himself, he may have had anti-slavery leanings. In 1828, a Robert Armistead was a signatory of the "Memorial of Inhabitants of the District of Columbia, praying for the gradual abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia." His name appears on the same page as other slaveholders working at the Navy Yard. The memorial criticized the separation of families and the enslavement of those entitled to freedom, such as having a term of service ignored or thwarted due to sale, and free people being kidnapped or sold without inquiry into their right to freedom. If this memorial reflected the beliefs of the Robert Armistead who was the slaveholder of Mary Bell and her children, he would have been unhappy to learn of the ways his widow prevented them from claiming their freedom two decades later.11

Armistead's second wife, Susanna (Susan), may have had some connection to the Greenfield family who claimed the Bells. In one newspaper article that appeared after the Pearl incident, she was mistakenly referred to as "the widow Greenfield." Susan's maiden name was very likely Marshall. In the court papers for Mary's case, there is a reference to a deed of gift between an unnamed Marshal to Susannah Marshal, and the first of Robert and Susan's daughters was given the name Susannah Marshall Armistead.12 When Ann Bell petitioned for her freedom, another of Robert and Susan's daughters, Sarah Jane, appeared as a witness for Greenfield, as well as an Elizabeth Marshall. Many of the same witnesses in Ann's case later appeared as witnesses for Susan in the petition of Mary's daughter.13

By September 1835, Daniel and Mary had six children: Andrew (11), Mary Ellen (8), Caroline (6), George W. (4), Daniel (2), and Harriet (3 months). Mary resided with Daniel and their three youngest children, and Robert Armistead's health was failing. Robert had since left his job at the Navy Yard and been forced to give up the shop he opened in his home. The Armistead family fell into poverty, despite Susan's efforts to support it.14 Perhaps sensing the desperation of the Armisteads and fearing for his own family upon the death of Robert, Daniel may have begun plotting the emancipation of his wife and children. He knew all too well how the death of a slaveholder could jeopardize their precarious security. He was right to have worried.

Perhaps sensing the desperation of the Armisteads and fearing for his own family upon the death of Robert, Daniel may have begun plotting the emancipation of his wife and children. He knew all too well how the death of a slaveholder could jeopardize their precarious security.

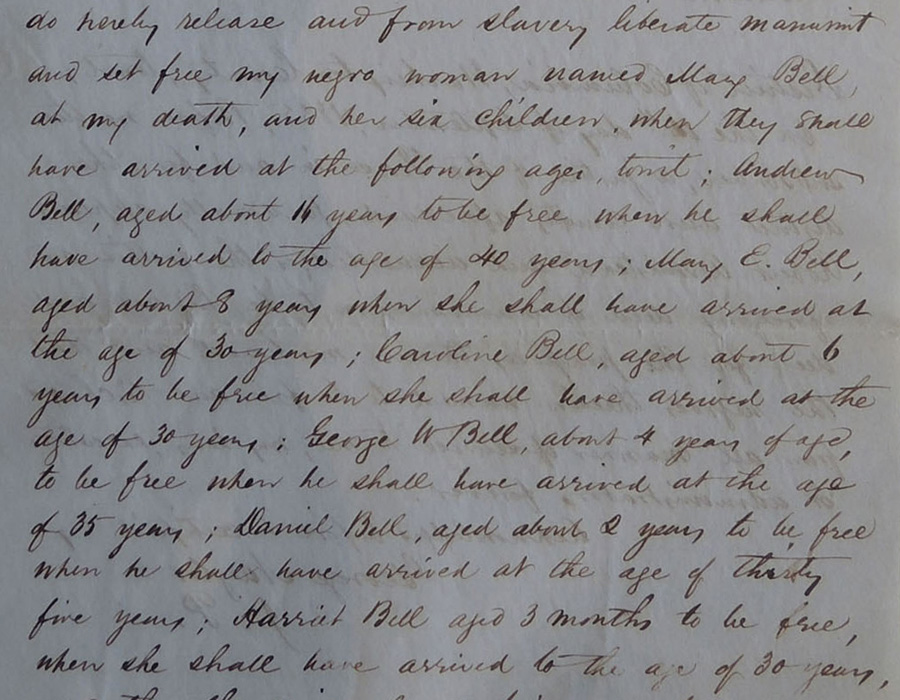

Robert Armistead died on or around September 16, 1835. Two days earlier, he signed a deed of manumission, stating that Mary Bell was to be set free upon his death, and establishing terms of service for her children: until the age of 30 for the girls and 35 for the boys, with the exception of the eldest, Andrew, who was to remain enslaved until he was 40 years old. The document was signed in the presence of George Naylor, a justice of the peace, and Richard Butt, the intendant of the Washington Asylum, the local almshouse.

Considerable drama preceded the signing of the deed. Sometime before his death, Robert left his home to reside at the almshouse, despite the objections of his wife, Susan. There, he was attended to by a physician, Edward Clarke, who served as one of the guardians of the poor. Susan Armistead later claimed that Clarke paid frequent visits to Robert to "prevail upon him [Robert] to execute a deed of manumission." According to Susan, Robert refused to do so without her presence and consent. Susan's later testimony suggested the she held Daniel Bell responsible for Robert's departure for the asylum, and that he was part of a conspiracy to deprive her of her husband's human property. She claimed that Daniel called at the gate of their yard and presented Robert with a letter. When Daniel was asked by one of the Armistead daughters if the letter was from their sister in Virginia, Daniel reportedly replied, "Yes." Susan claimed that Robert was secretive about the letter, and he began packing his trunks the next day. When a cart eventually arrived to take him away, Robert presented the cart man with the mysterious letter Daniel had given him two days before, and they departed for the almshouse.15

If Mary disputed any of Susan's claims, it was not recorded in the case papers, though later, in a motion for a new trial, she declared that she could prove that Dr. Clarke was ill and bed-ridden during the time that Susan claimed he solicited Robert to sign the deed. Mary explained that while Robert was at the Washington Asylum, he was visited by a justice of the peace—presumably George Naylor—who either prepared there or brought with him the deed of manumission. Daniel was present, and when directed to by Robert, he retrieved from a chest a bible or prayer book where the names and ages of Mary and the children were recorded. The information was written into the deed, which was read back to Robert by the justice of the peace, and then signed and acknowledged. Robert died two days later, and on September 21, Mary was granted a certificate of freedom and registered as a free woman by the clerk of Washington County.16

But the drama did not end there. When Daniel Bell's slaveholder learned of Mary's manumission and the gradual emancipation of their children, he or she sold Daniel to speculators. Slave traders came to his shop in the Navy Yard, knocked him to the floor, and hauled him off in shackles to a slave pen on Seventh Street, most likely the notorious private jail owned by William H. Williams. Williams was the man who purchased James Ash from Gerard T. Greenfield four years later. It is possible that Greenfield was the slaveholder who sold Daniel, as he held numerous enslaved people in bondage from the estates of his aunts and uncles, including Ann Bell and James Ash. It was, perhaps, the excitement surrounding Daniel and his family that prompted Greenfield to try to claim Ann and her sons about a year later.17

As a result, on September 24, 1835, Daniel Bell petitioned for freedom in the circuit court against John Stephenson, a constable for the District. Edward Clarke, the physician who allegedly examined Robert Armistead at the almshouse, entered security for the cost of Daniel's petition. Apparently a friend or acquaintance of the Bells, Clarke later appeared as a witness for Ann in her suit. One month after the petition was filed, Daniel's counsel dismissed the case. He and his allies had arranged for a Marine colonel in the neighborhood to purchase him, with the understanding that Daniel would make payments to buy his own freedom. The identity of the colonel is unknown, but one likely candidate is Charles R. Broom. Broom appeared in the 1830 census as a neighbor of Robert Armistead. In 1840, Broom's household contained an enslaved man, age 24-35. This could be Daniel Bell, although it is very likely he continued to live in the same manner he did prior to his new arrangements, with his wife and younger children.18

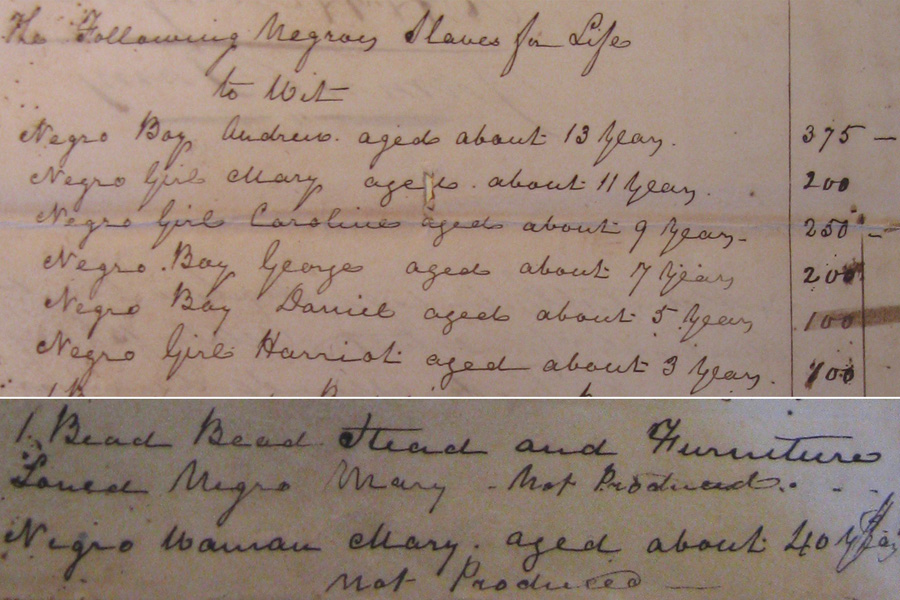

By 1838, it became clear that Susan Armistead did not plan to recognize the deed of manumission signed by her late husband and recorded with the clerk of the court. When the appraisement of the personal estate of Robert was conducted, the Bell children were inventoried as "slaves for life." The eldest, Andrew, was valued at $375, Caroline at $250, Mary Ellen and George at $200, and the youngest, Daniel and Harriet, valued at $100. Mary was listed on the inventory as "not produced," in addition to one bed, bedstead, and furniture that had been loaned to "Negro Mary." The total amount of Robert's personal estate was $1,299.25. Only $74.25 of it was not in human property. Susan appeared before the Orphan's Court one year later to file the inventory. If her 1839 account is to be believed, since Robert's death, Susan kept Caroline, George, and Harriet in her home. The eldest children were hired out, with Andrew bringing in $2 per month between 1836-1839, Mary Ellen bringing $1.50 per month for one year, and Caroline bringing in $1.50 per month for five months, with two more months at a rate of $2 per month. There was no mention of young Daniel who may have still been living with his parents.19

In March 1840, Ann Bell's petition for freedom finally went to trial. Susan's daughter, Sarah Jane, appeared as a witness for the defendant, Gerard T. Greenfield. It is unknown what her testimony entailed, nor the exact nature of the Armistead family's connection to the Greenfields. The question put to the jury seems to have been whether or not Ann was freed by the 1815 will of Gabriel P. T. Greenfield, the defendant's uncle. Probate was refused by the Maryland Court of Appeals, and yet the jury apparently found enough evidence in Ann's having gone about as free, purchased real property, built a house, hired a servant from Greenfield, and committed other acts "inconsistent with the condition of slavery" to render a verdict in favor of her freedom on April 15.20 Even though she had been living as free for nearly two decades, Ann Bell and her two sons, Daniel and David, now had their liberty sanctioned by the courts.

Her brother was close to his own freedom as well. Daniel Bell had almost paid off his $1,000 purchasing price, when the colonel he had made arrangements with died.21 Daniel learned then that the colonel had mortgaged him to his sister-in-law for $1,000, and she demanded the full sum now from Daniel. A lumber merchant named Thomas Blagden intervened and was able to get the sum reduced to five or six hundred dollars. Blagden lived in the neighborhood near the Navy Yard and perhaps had contracts there. Somehow, he became acquainted with Daniel and had been endorsing his notes for him as he made payments to the colonel. Navy payroll records for January 1848 showed that Daniel worked 22.5 days and earned $31.20 in wages for the month. At that rate, the price for his freedom was nearly two years' wages. In all, it took Daniel another five years to buy back his liberty. When all was paid and accounted for, his receipts showed that he paid a total of $1,630 for his freedom.22

When all was paid and accounted for, Daniel Bell's receipts showed that he paid a total of $1,630 for his freedom, more than four years' wages.

In June 1843, Susan Armistead filed a petition in the Orphan's Court for an appraisement of the Bells so that they could be divided among her children, and the court ordered the valuation and distribution to take place. Mary Bell was likely made aware of this, and a couple months later, she presented evidence of her title to freedom to the Register of the City of Washington, who provided her with a certificate of freedom. It should have protected her liberty, but it did not.23

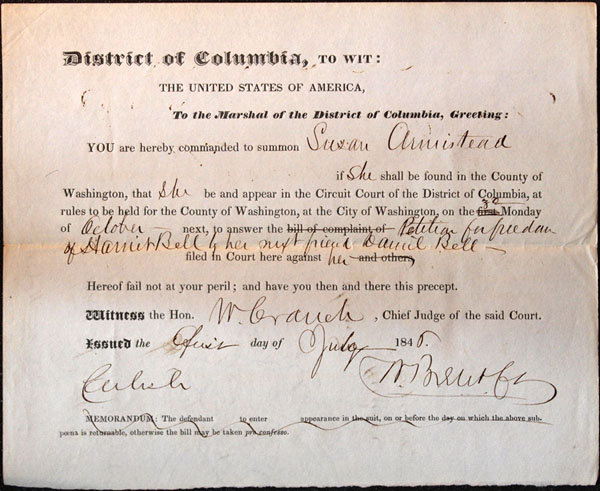

Almost a year later, on September 13, 1844, Mary filed a complaint in chancery against Susan Armistead, James C. Deneale, and David Little to go along with the petitions for freedom she filed on behalf of herself and her daughter, Eleanora, who had been born August 3, 1839. Armistead, Deneale, and Little were "pursuing" the Bells "with the avowed intention of selling them," and Mary requested an injunction to prevent them from removing her and Eleanora from the court's jurisdiction until their petitions for freedom were decided. The injunction was issued, and the case eventually went to trial in October 1847. In the mean time, Daniel and Mary welcomed their eighth child, Thomas. Yet Susan Armistead made further attempts to separate the Bell family. She seized Eleanora, despite the seven-year-old being born after Mary gained her freedom, and also planned to send Harriet out of the District, likely to one of her children in Virginia or Maryland. Daniel filed a petition for freedom as the next friend of Harriet and also requested an injunction, which was granted.24

When Mary's case finally went to trial, the matter put to the jury seemed to be whether or not Robert was of sound mind and capable of disposing of his property when the deed of manumission was signed. The jury evidently felt there was evidence of force or coercion used, and they found in favor of Susan Armistead. Mary filed a motion for a new trial on the grounds that she had new evidence to show cruel treatment committed by Susan against Robert, that Robert steadfastly denied his wife's pleas to revoke the deed before he died, and that Edward Clarke, who Susan claimed was instrumental in pushing the signing of the deed, was ill and confined to his bed during the time alleged. Another trial was held in March 1848, but by then, Daniel had begun making plans to take the freedom of his family into his own hands.25

In February 1848, a ship captain residing in Philadelphia named Daniel Drayton received a letter through an intermediary detailing the plight of the Bell family. Drayton was known among anti-slavery circles for having transported an enslaved woman and six children out of Washington, D.C., to Frenchtown, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore. Having no ship of his own, Drayton declined to intervene on the Bells' behalf, but when he was approached two weeks later by the same intermediary, Drayton agreed to help and began to seek out a vessel. He encountered a man named Edward Sayres who was sailing a schooner called the Pearl. Drayton arranged to pay Sayres $100 to charter his ship to Washington and back to Frenchtown. There, the Bell family would be met by friends and conveyed to freedom in Philadelphia.26

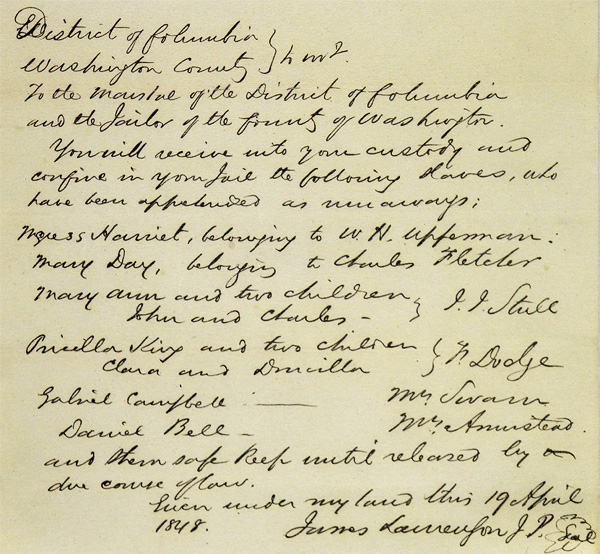

What had begun as a means to keep his family intact grew exponentially as word of Daniel's plan spread throughout the city. By the time the Pearl pulled away from the isolated wharf somewhere near Seventh Street on the night of April 15, 1848, the number of freedom seekers had swelled from Mary and her eight children and two grandchildren to over 70 people. During the early hours of the morning of April 18, a steamer sent out by slaveholders who had learned of the plot overtook the Pearl. By 7:30 AM, the vessels were docked back in Washington, and the captives were marched through the streets to the city jail.27 Somehow, a few managed to slip away but were soon caught again. The next day, a warrant was issued to the Marshal of D.C. and Jailor of Washington County to confine a group of runaways from the Pearl that had been apprehended. Among the ten names listed was fifteen-year-old Daniel Bell.28

Two days later, a congressman from Albany, New York, named John S. Slingerland, passed the railroad depot near the Capitol where some of the fugitives were being held before being sent to Baltimore for sale. He witnessed Daniel Bell's plea for his wife's release and wrote about it in a letter to the editor of the Albany Evening Journal. His account was published in newspapers around the North under the headline "Horrors of Slavery." Later, this community of sympathetic supporters would help raise funds to reimburse the $400 Thomas Blagden advanced to Daniel in order for him to purchase Mary and one of their children. One such supporter was Alexander Taverns, a free black living in Washington, D.C., who paid the enormous sum of $75. In all, Daniel was only able to save Mary and two of their children, Thomas, and most likely, Harriet. The rest remained enslaved and were sold as far south as Louisiana and Mississippi.29

Eleanora had not been sold away, and was still enslaved by Susan Armistead. On March 26, 1849, nearly one year after her failed exodus, she filed another petition for freedom on the grounds that she had been born after Mary obtained her freedom under a deed of manumission that had been certified by the court. Susan apparently had plans to send Eleanora to Norfolk, Virginia. In spite of the way the courts had failed the family in the recent past, the Bells may have felt the law was their only recourse to keep what was left of their family together. For reasons unknown, the petition was filed again one year later on April 18, 1850, two years to the day after the Pearl was brought back to Washington. Susan was summoned in December 1850, but when she failed to attend court, she was held in contempt and an attachment was issued. The attachment was returned as not found, and according to Eleanora's counsel, Susan had "absconded or secreted herself [away] to avoid process of the court." She evidently resurfaced, and on December 4, 1851, a jury rendered a verdict in her favor, deciding that Robert Armistead was not of sound mind when the deed was executed. Eleanora remained enslaved.30

While Eleanora's case was pending, another member of the Bell family turned to the courts. Daniel's sister, Caroline, who had been living as a free woman for thirty years, suddenly found herself being claimed by the administrator to the estate of Greenfield heir Susan G. Beall. Susan was the daughter of Ann T. Beall (née Greenfield), who bequeathed Caroline to her daughter in 1832. By all appearances, Susan Beall had never laid claim to Caroline in life, but her heirs would not be denied after her death. The outcome of Caroline's petition is unknown.31 But slavery's days in Washington, D.C., were numbered.

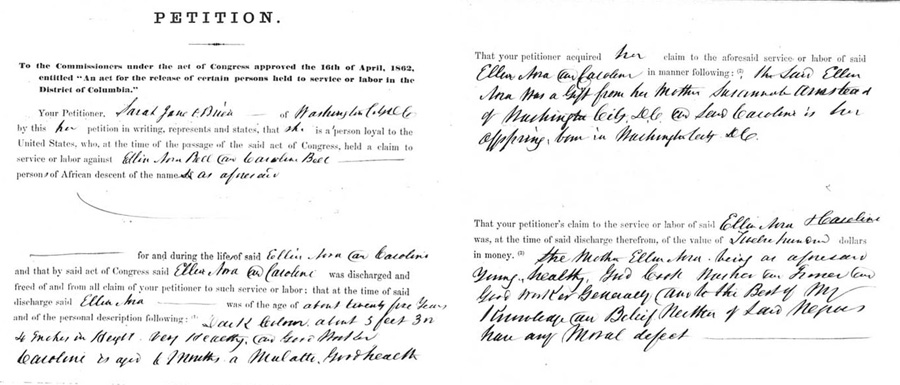

Ten years after the court denied Eleanora Bell her freedom, Abraham Lincoln signed the Compensated Emancipation Act on April 16, 1862, freeing the approximately 3,000 enslaved men, women, and children in the nation's capital. Eleanora, now nearly 23, and her 6 month old daughter, Caroline, were among those freed. Since her family's attempt at freedom on the Pearl, she remained in the possession of Susan Armistead, who resided only about a mile and a half away from the home of her parents. In February 1862, Susan gifted ownership of Eleanora to her daughter, Sarah Jane O'Brien, with whom she was living. She also gifted Eleanora's infant daughter to her eight-year-old granddaughter, Mary Catherine O'Brien. In her petition for compensation, Sarah Jane valued the service of Eleanora and Caroline at $1,200, stating that Eleanora was "young, healthy, [a] good cook, washer and ironer, and [a] good worker generally." Sarah Jane was compensated a total of $438 for them both: $394.20 for Eleanora and $43.80 for Caroline.32

Freedom likely came to Eleanora's eldest sister, Mary Ellen, during the Civil War. In the aftermath of the Pearl, she was sold to western Mississippi. By January 1864, she had four children and was already widowed. Her husband, Jordan Dawley, enlisted in the Union army on October 1, 1863, at Vicksburg, and was assigned to Company D of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry (African Descent). Three months after his enlistment, the 45-year-old succumbed to pneumonia. Mary Ellen survived the war, however, and was able to send word back to her parents in D.C.33 In his 1875 will, Daniel Bell left the entirety of his estate to his "well beloved and devoted wife, Mary." Upon her death, he devised his estate to be disposed of and the proceeds give in equal parts to his descendants: his daughter, Caroline; his son, Daniel; his daughter, Mary Ellen; his grandchildren by Harriet; and his granddaughter by Eleanora, Caroline.

Although the Bell family fought for decades to keep their family together in the face of enslavement, the slave trade, and war, slaveholders separated them indiscriminately, sold them south, and some of the children were never reunited with the family. There was no mention in Daniel's will of Andrew and George, nor their families, suggesting that they were never heard from again following their sale in 1848. Also missing was Thomas, who may have died sometime after the 1850 census was taken. Harriet must have died between 1870 and 1875. She married and had four children who were not mentioned by name in Daniel's will. It seems that Eleanora had no more children after Caroline, and she likely died before 1870. Young Caroline was living with her great-aunt, Ann Bell, in the 1870 census, and was referred to as Carrie Bell in an 1884 petition filed in Daniel's estate.34

Although the Bell family fought for decades to keep their family together in the face of enslavement, the slave trade, and war, slaveholders separated them indiscriminately, sold them south, and some of the children were never reunited with the family.

Even though Mary Ellen was able to get back in touch with her family, Daniel stated in his will that he had not heard about her "whereabouts or life or death" in three years. But by 1884, she was reconnected again, and mentioned by her sister in a document in her father's estate. She had remarried, to a man named Alex Robertson or Robinson, and was still residing in western Mississippi.35 It is assumed that Daniel, Jr., was able to regain contact with his parents not too long after the war based on his presence in his father's will. In 1883, Mary Bell withdrew $75.55 from the estate and sent it to Daniel in Natchitoches, Louisiana, where he was living with his wife and eight children. It is unclear what happened to Caroline or her two children, Catherine and John, in the wake of the Pearl affair. But after the war, Caroline reunited with her parents, and she and her husband, John Green, often served as witnesses for Mary when she received funds from Daniel's estate.36 Daniel Bell died in March 1877, leaving behind a personal estate worth more than $250 and a house at 319 F Street SW. Their home had a parlor, a dining room, kitchen, and second floor bedrooms where Mary lived with Caroline and her husband during the last years of her life. Mary died sometime between April and August 1884.37

The Bell family's road to freedom was full of missteps and reversals, complications and losses. There were few triumphs. For most of the family, the law provided no sanctuary. Mary's freedom was stripped from her. Her children were enslaved for life. The family was separated numerous times. Only Ann Bell won her case in court. For the Bells and for other families in this period, the freedom suits did not lead to favorable verdicts. Instead, they created opportunities for the families to negotiate their freedom. Or if necessary, seize it by other means.

For a more dynamic presentation of the Bell's freedom-making attempts from 1835-1850, visit their Story Map.

Endnotes

1. John H. Slingerland, a congressman from Albany, New York, witnessed the scene and wrote about it in a letter that was reprinted in abolitionist newspapers across the country. A later article identified the man as Daniel Bell, a native of Prince George's County, Maryland, who had himself only been free from slavery for about a year. "The Recaptured Fugitives," The North Star, May 12, 1848; "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848. [back]

2. Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: William Morrow, 2007), 6; Josephine F. Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 1. [back]

3. The story of the Bell family, incomplete as it may be, is presented here in the hopes that one day, future researchers will be able to connect the pieces and fill in gaps using data and means not yet uncovered. [back]

4. Daniel Bell and Ann Bell in 1850 United States Federal Census, Washington Ward 5, Washington, District of Columbia, dwelling 236, families 279, 280, NARA Roll M432_57, Page 108A, Image 222, digital image, Ancestry.com; Ann Bell, Daniel Bell, and David Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, in O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, ed. William G. Thomas III, et al. [back]

5. James Ash v. William H. Williams, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas, et al. Some court documents misspell Maria Amne's name with variations of "Maria Anne," but her name is spelled "Maria Amne" and "Maria Amna" in her will. Other Greenfield probate records spell it "Mariamna," "Marianna," and "Maria Mima." [back]

6. "Jury Instructions," Ann Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas, et al. [back]

7. There is a discrepancy across the historical record for the year of Lucy's birth. Her tombstone gives her age as 99 years in 1862, putting her birthdate sometime around 1763. The 1850 census places her birth year in about 1773, while the 1860 census has about 1766. Find A Grave, Memorial Page for Lucy Bell, no. 114202114, citing Congressional Cemetery, Washington, District of Columbia, District Of Columbia, USA, maintained by Paul Hays (contributor 47393402); Historic Congressional Cemetery, "Search Internment Records"; 1850 United States Federal Census, Washington Ward 5, Washington, District of Columbia, dwelling 236, family 280, NARA Roll M432_57, Page 108A, Image 222, digital image, Ancestry.com; 1860 United States Federal Census, Washington Ward 7, Washington, District of Columbia, dwelling 431, family 464, NARA Roll M653_104, Page 765, digital image, Ancestry.com.

Subsequent information on Lucy and her children is derived from the following probate records unless otherwise mentioned. Will of Gerrard T. Greenfield, October 4, 1796, Maryland Register of Wills Records, 1629-1999, images, FamilySearch, citing Prince George's County Wills, Liber T, No. 1, 1770-1808, pp 390-391; Will of Ann Greenfield, March 11, 1809, Maryland Register of Wills Records, 1629-1999, images, FamilySearch, citing Prince George's County Wills, Liber TT, No. 1, 1808-1833, p 29; Inventory of Walter Greenfield, February 14, 1814, Maryland Register of Wills Records, 1629-1999, images, FamilySearch, citing Prince George's County Wills, Liber TT, No. 1, 1808-1833, p 544-546; Inventory of Sabina Greenfield, January 11, 1822, Maryland Register of Wills Records, 1629-1999, images, FamilySearch, citing Prince George's County Wills, Liber TT, No. 6, 1808-1833, p 46; "Will of Maria Anne T. Greenfield," September 16, 1824, Ann Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas, et al. [back]

8. Harrison Dwight Cavanagh, Colonial Chesapeake Families: British Origins and Descendants, 2nd Edition, Volume 2 (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, 2017), 173. [back]

9. Surnames for the Bell sisters in later documents are as follows: Harriet Ashe, Caroline Butler, Kitty Carroll, and Eleanor Tyler. Caroline married a man named William Butler, and it is assumed here that the James Ash residing with the Bells in 1850 and formerly claimed by the Greenfield family is the husband of Harriet. The other surnames are likely married names as well, however, no spouses have been located. Record for Daniel Bell in Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874, Washington, D.C., National Archives and Records Administration, M816; Record for Caroline Butler in Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, M816; Last Will and Testament of Ann Bell, 19 Sept. 1871, Probate Records (District of Columbia), 1801-1930, District of Columbia Register of Wills, Washington, D.C. [back]

10. One of Lucy's neighbors in the census was Charles B. Hamilton, a Navy surgeon attending the Marine Corps in the Navy Yard. His address in the 1822 directory gives us an idea of the location of the Bell household. 1820 Federal Census, Washington Ward 5, Washington, District of Columbia, Pages 88-90, M33, Roll 5, digital image, Ancestry.com; Judah Delano, The Washington Directory (Washington: William Duncan, 1822), 41, 18. [back]

11. District Of Columbia, Memorial of inhabitants of the District of Columbia, praying for the gradual abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia (Washington: Printed by Gales & Seaton, 1828). [back]

12. Burial records for Congressional Cemetery show that in 1892, Robert Armstead and Elizabeth and Josiah Marshall were moved from Eastern Methodist Cemetery and re-interred at Congressional Cemetery in a plot next to Susanna Armistead's. "Armistead Family: Bible Entries," William and Mary College Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1902): 144-145; "Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions," December 6, 1847, pp 1-2, Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas, et al.; Historic Congressional Cemetery, "Search Internment Records"; Find A Grave, Memorial Page for Josiah Marshall, no. 187871756, citing Congressional Cemetery, Washington, District of Columbia, District Of Columbia, USA, maintained by Historic Congressional Cemetery Archivist (contributor 46570972). [back]

13. "List of Defendant's Witnesses," Ann Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas, et al.; "Minute Book Entry," December 3, 1851, Eleanora Bell v. Susan Armstead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas, et al. [back]

14. "Deed of Manumission," September 14, 1835, and "Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions," December 6, 1847, pp 3-4, 7, 10, Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

15. "Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions," December 6, 1847, Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

16. "Motion for New Trial," December 14, 1847, and "Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions," December 6, 1847, Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

17. "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848. For the location of Williams' jail, see "Clay A Better Abolitionist Than Birney," Daily Globe, October 29, 1844, p 3 and David Fiske, Clifford W. Brown, and Rachel Seligman, Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years A Slave (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2013), 51. [back]

18. Daniel Bell v. John Stephenson, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al.; "Petitioner's Bills of Exceptions," December 6, 1847, p 10, Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

19. Estate of Robert Armstead, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 1832, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

20. Ann Bell, Daniel Bell, and David Bell v. Gerard T. Greenfield, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

21. An article published in many anti-slavery newspapers following the Pearl incident stated that the colonel was ordered to Florida where he died. Charles Broom, the likely candidate for the colonel, did command troops who were stationed in Florida, but Broom was detached to Washington, D.C., when he died on November 14, 1840. Florida, Fort Brooke, 1824 Jan - 1840 Dec, Returns From U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M617, 1,550 rolls), Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780s-1917, Record Group 94, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Charles R. Broom obituary, The Madisonian, November 17, 1840. [back]

22. The 1848 article stated that Daniel "got his freedom papers only last year sometime." But he likely obtained his freedom earlier than that, as he was able to appear as the "next friend" of his daughter Harriet in her freedom petitioned filed July 1, 1846. "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848; John G. Sharp, African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard, 1799-1865 (Concord, CA: Hannah Morgan Press, 2011), citing RG 71, Records of the Bureau of Yards and Docks 1784-1962, Shore establishment payrolls, 1844-1899, WNY Payroll, January, 1848, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

23. Estate of Robert Armistead, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 1832, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

24. The verdict in Mary's case was delivered in December 1847, but the court term began in October. Mary Bell v. Susan Armstead, James C. Deneale, & David Little in Loren Schweninger, ed., Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks: Petitions to Southern Legislatures and County Courts, 1775-1867 [microfilm], Series II, Part B, Roll 15, #20484405; "Petition," July 1, 1846, Harriet Bell v. Susan Armistead, in Schweninger et al., Race, Slavery and Free Blacks, Series II, Part B, Roll 15, #20484601; Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

25. Mary Ricks writes that the new trial was granted, but before proceedings began, an appellate court upheld the jury's verdict. She does not give a citation for the appellate court information. The case papers for Mary's petition were filed at the National Archives in the March 1848 term of Civil Trials, but do not contain any documents from the new trial. It is unclear whether a new trial was held in the circuit court or an appellate court, as reported by Ricks. In his opening argument to the jury in the trial against Daniel Drayton, who captained the Pearl, Horace Mann stated that the Pearl arrangements were made while the new trail was pending. Mary Ricks, Escape on the Pearl, 60; Mary Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al.; Horace Mann, Slavery: Letters and Speeches (Boston: B. B. Mussey & Co., 1851), 116-117. [back]

26. Josephine Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 52-53; See also Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton (Boston: Bela Marsh, 1853), 24, 28. [back]

27. For a more detailed account of the Pearl incident, see Pacheco, Ricks, and Harrold. Ricks, Escape on the Pearl, 16, 30, 76-85; Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton, 29-39; Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2002), 116-118; Pacheco, The Pearl, 54-63. Mann, Slavery: Letters and Speeches, 116-117. There is a discrepancy in the number of people who attempted to escape enslavement aboard the Pearl. Initial newspaper accounts reported the number at "38 men and boys, 26 women and girls, and 13 children—77 in all." In the statement of Evidence for Indictment 119 against Daniel Drayton, it was stated that there were "76 negroes in the hold" of the ship. But in the presentment of the jury, the number of "negro slaves" Drayton was accused of stealing was given as 74. Daily Union, April 19, 1848; "Statement of Evidence and 3rd Bill of Exceptions," p 3, and "Presentment," June 27, 1848, U.S. v. Daniel Drayton in RG 21, Records of the District Courts of United States, Entry 45, U.S. Criminal Court for D.C. Criminal Appearances 1838-61, Box 4, June Term 1848, Appearances, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

28. U.S. v. Daniel Drayton in RG 21, Records of the District Courts of United States, Entry 45, U.S. Criminal Court for D.C. Criminal Appearances 1838-61, Box 4, Criminal Trials, March Term 1849, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

29. See, for example, the Daily Republican (Springfield, Massachusetts), April 28, 1848. "The Recaptured Fugitives," The North Star, May 12, 1848; "Beauties of the Slave System," The North Star, October 13, 1848; Ricks, Escape on the Pearl, 108. [back]

30. Eleanora Bell v. Susan Armistead, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. [back]

31. Caroline Butler v. Fielder Magruder, in O Say Can You See, ed. Thomas et al. Caroline was married to a man named William Butler, who, at the time of his death of pneumonia in 1870, was employed as a boatman. Record for Caroline Butler in Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, M816; Caroline Butler v. Fielder Magruder in Race & Slavery Petitions Project, Petition 20484906; Federal Mortality Census Schedules, 1850-1880, and Related Indexes, 1850-1880, T655, Roll 5, Washington Ward 2, District of Columbia, U.S. Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850-1885, Ancestry.com. [back]

32. "Petition of Sarah Jane O'Brien," May 5, 1862, in Civil War Washington, citing Records of the Board of Commissioners for the Emancipation of Slaves in the District of Columbia, 1861–1863, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 217.6.5, Records of the General Accounting Office; U.S. Congress, House, Emancipation in the District of Columbia, 38th Cong., 1st Sess., 1864, Ex. Doc. 42, p. 17. The May 5 petition of Sarah Jane O'Brien reported Eleanora's age as "about 25," but going by the birthdate provided in Eleanora's petition for freedom, her exact age would have been 23. For more about the Compensated Emancipation Act, see Kenneth J. Winkle, Lincoln's Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, DC (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013), 268-279. Winkle notes that Eleanora's younger sister was also emancipated, but that Caroline Bell from Howard County, Maryland, is of no known relation to this Bell family. Eleanora's sister, Caroline Bell, was older than her, and about 33 years old in 1862. [back]

33. Record for Mary Dawley in Registers of Signatures of Depositors in Branches of the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company, 1865-1874, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, M816; Jordan Dawley, Co G., 352 USCT, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the United States Colored Troops: Infantry Organizations, 47th through 55th; Microfilm Serial: M2000; Microfilm Roll: 112. [back]

34. Last Will and Testament of Daniel Bell, December 27, 1875, Washington, D.C., Wills and Probate Records, 1737-1952, Ancestry.com; Harriet Snow in 1870 U.S. Federal Census, Washington Ward 7, Washington, District of Columbia, M593, Roll 126, Dwelling 2764, Family 2891, Ancestry.com; Petition of Caroline Green filed in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (Probate), August 30, 1884 in Estate of Daniel Bell, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 8091, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

35. Mary Robertson in 1880 United States Federal Census, Beat 5 Warren, Mississippi, Washington Ward 5, Washington, District of Columbia Roll 667, Page 626A, digital image, Ancestry.com; Petition of Caroline Green filed in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (Probate), August 30, 1884 in Estate of Daniel Bell, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 8091, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

36. Estate of Daniel Bell, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 8091, National Archives, Washington, D.C. [back]

37. Estate of Daniel Bell, RG 21, Entry 115, O.S. Case File 8091, National Archives, Washington, D.C. The last time Mary appeared in the estate documents is April 18, 1884. On August 30, Caroline filed a petition against administrator George W. Snow and Mary is not named as one of Daniel Bell's heirs. City directories show John Green residing at 319 F Street beginning in 1881. See, for example, William H. Boyd, Boyd's Directory of the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C., 1881), 385. [back]