About

This project collects, digitizes, and makes accessible the freedom suits brought by enslaved families in the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, Maryland state courts, and the U.S. Supreme Court. In making these documents accessible, the project invites you to explore the legal history of American slavery and the web of litigants, jurists, legal actors, and participants in the freedom suits. This project places these families in the foreground of our interpretive framework of slavery and national formation.

Why are we doing this? First, printed legal sources such as Judge William Cranch’s reports on the cases in the D.C. Circuit Court have been cited routinely in appellate decisions and legal briefs, as well as relied upon by legal historians for years. Yet much information—the names, occupations, and experiences—about enslaved and free African American litigants did not make it into Cranch's volumes. Cranch rarely included the last names of African Americans, did not publish the original papers for their freedom cases, and focused only on the handful of cases that he thought established legal procedures and rules. The result is a historical and genealogical erasure that needs repair.

Second, freedom suits presented a significant legal challenge to slavery and slaveholders. Freedom suits were, in fact, common across the Americas—thousands of cases were brought in the U.S., Brazil, Cuba, and the French and British Caribbean. In the U.S., African American enslaved families accumulated legal knowledge, legal acumen, and experience with the law that they passed from one generation to the next. The freedom suits they brought against slaveholders exposed slavery a priori as subject to legal question. The suits in Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, raised questions about the constitutional and legal legitimacy of slavery, and by extension, affected slavery and law in Maryland, Virginia, and all of the federal territories. Fundamentally, slavery was more susceptible to legal challenge than many scholars have accounted for.

Third, these cases and the documents about them reveal the terrible scale and scope of the domestic interstate slave trade in U.S. history and the ways that families used the law, especially to resist the slave trade and the breakup and separation of their families.

Encoding People & Relationships

The project attempts to document and infer relationships between every individual named in the legal records, to assemble a complete set of ascribed relationships for each individual, and to make visible connections in the freedom suits, including the networks of relationships of the enslaved and free. Using the D.C. Circuit Court case papers and other records, we attempt to reconstruct the situation for the participants in each freedom suit.

There are significant challenges. First, the records are fragmentary and incomplete. Second, the records we have are ones produced by and through a legal culture controlled by slaveholders.

This digital archive, therefore, is an alternate archive, one designed to put the evidentiary fragments in relation to one another and to expose and simultaneously move beyond the legal culture that produced them. It is both an archive and a shadow archive, a diptych that shows in relief what would otherwise remain hidden.

To this end, every individual mentioned in the case papers has an individual project record. We expose the instability of each person's described attributes such as status, color, gender, occupation, and residence, by linking each instance of ascription in the documentary record. Attributes change over time and from describer to describer—they are presented in one way at one time and in another way at another time, depending on the situation and the author.

Just as important, every relationship of every person, as expressed in these documents (enslaved by, parent of, child of, neighbor of, witness for, client of, . . .), is encoded into a standard, extensible, and widely sharable format. For further information, see Data Download & Query.

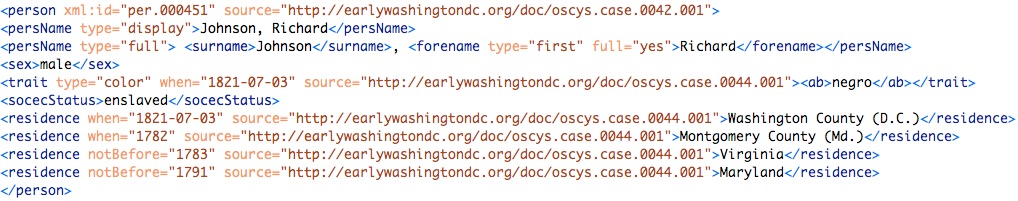

Here's an example of the TEI encoding of people:

Each descriptive entry points to the source document for each attribute. Each attribute can have multiple instances. Name, age, and especially color appeared differently in different documents over time. Residences of the enslaved are named and can be tracked.

Our encoding of the relationships in these freedom suits begins to reveal the extraordinary range of contacts, descriptions, and connections in this social and legal world. In 509 petitions for freedom, we have found the names of over 4,800 individuals and 55,000 relationships.

Funding & Support

Funding and support are provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and the University of Maryland's Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities.