Frequently Asked Questions

What is a freedom suit?

A freedom suit is a legal case brought before a court by an enslaved person pursuing their freedom from a slaveholder.

It begins with the filing of a freedom petition.

Petitions for freedom vary in length and language. But most contain the same basic elements. We will use the petition filed in Ann Bell and her children v. Gerard T. Greenfield as an example.

After the petition is filed, a summons is served on the slaveholder by the marshal of D.C., notifying them of the lawsuit.

What follows is the discovery process, where each of the parties gather evidence to support their claims. This typically takes the form of depositions—sworn statements from individuals with information relevant to the case—but wills, manumission papers, and other documents are sometimes produced.

When the case comes to trial, a jury is empaneled. Once each side has presented their evidence, the attorneys will provide instructions to the jury on which they must base their verdict. These instructions must be agreed upon by the attorneys and often go through many revisions.

A verdict is reached and a judgment made.

| To the Honorable the Judges of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia for Washington County | The caption: this part of the petition identifies the court and the court's location. |

| The petition of Anne Bell, for herself and her two children, Daniel and David respectfully Sheweth: | The petition begins by identifying who is filing the petition. Here, Ann is also filing on behalf of her children. If the petitioner is a minor, the petition will be filed by their “next friend,” a term that referred to a person who worked on behalf of the petitioner. Ann Bell's brother, Daniel, acted as his daughter's next friend when she filed her petition. See Harriet Bell v. Susan Armistead. |

| That your petitioner is entitled to her freedom and is claimed and held as a slave for life by a certain Gerard T. Greenfield. | Next, the petitioner declares who they are petitioning for their freedom against. Occasionally, they will also identify their claim to freedom. Ann Bell does not do so here. |

| Your petitioner therefore prays your honors to grant her the United States Writ of Subpoena in the usual form to be directed to the Marshal of the District of Columbia, so that the said Gerard T. Greenfield may be summoned to answer this petition, and your petitioner will pray. | The petition closes with a prayer, a request to the court that something take place. In this instance, that the court issue a subpoena, requiring Gerard Greenfield to appear in court and answer to Ann Bell's claim to freedom. |

| G L Giberson Atty for Petitioner |

The attorney who prepared and filed the petition will sign his name. |

How could an enslaved person sue in court?

A petition for freedom was a civil suit. Such cases arose between parties as matters of private law, or equity, and drew on a long tradition of common law precedent that no person could be deprived of his or her liberty without cause. "Petitions" were a separate form of common law pleading before the court, asking the court to intervene in order to obtain a just result.

Petitions were listed separately in the Maryland dockets under their own heading. In Maryland, the General Assembly passed its first law regulating petitions for freedom in 1791. The "Act concerning petitions for freedom" required that "similar" suits by the same family be dismissed if they have reached resolution in another county. In various ways, the General Assembly tried to make petitions for freedom more difficult for enslaved plaintiffs. Two years later in 1793, the General Assembly stripped the General Court of jurisdiction over these cases and gave original jurisdiction to local county courts where slaveholders wielded more local power in juries and on the bench. Maryland's legislators further restricted petitions in 1796 by removing the right of appeal, "except as to matters of law, where the facts shall have been tried by a jury."

In Virginia, petitions for freedom were also civil suits but classified as "in forma pauperis," pleadings by persons without the means to otherwise bring a suit before the court.

Some black plaintiffs filed petitions for freedom based on ancestry, asserting that they were descended from a free woman and therefore held in bondage unlawfully. Others, because of manumission and various other contractual and legal mechanisms, were enslaved for fixed periods of time, say five or seven or ten years, to be freed at a later date under the terms of a contract, deed, or will, whether recorded in the court or not. When slaveholders reneged on these agreements, as they often did, enslaved persons might bring freedom suits that treated the dispute as a breach of contract. Finally, Maryland's 1783 statute outlawing the importation of slaves declared that "any person brought into this state as a slave contrary to this act, if a slave before, shall thereupon immediately cease to be a slave, and shall be free." Enslaved plaintiffs could sue for freedom under this act.

What were the grounds for a claim of freedom?

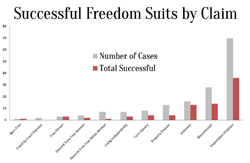

Petitioners in the Washington, D.C., court used a variety of arguments to secure their freedom. Of the cases in D.C. and Maryland on our site, the following claims for freedom were made, in order of frequency:

- Importation Violation

- Descent from a Free White Woman

- Descent from a Free Woman

- Manumission

- Property Dispute

- Term Slavery

- Kidnapping

- Living Independently

- Born Free

- Free Person

- Freed by Court Decision

How did petitioners get their attorneys?

It is clear that enslaved families kept track of who represented them, and that they were the ones who took the initiative to seek out attorneys. A group of attorneys in Maryland, beginning with Samuel Chase, Gabriel Duvall, and Jeremiah Townley Chase, represented hundreds of enslaved plaintiffs in the 1790s. As the number of freedom suits accelerated in that decade, the general court may have assigned attorneys or rotated assignments as plaintiffs sought to bring petitions.

In Maryland, attorneys were paid a flat fee based on the type of case. Initially, this meant that some plaintiff's attorneys in freedom suits could take cases on a contingency basis. In 1796, the Maryland General Assembly made such contingency fees more difficult for petitioners in freedom suits by requiring attorneys to pay "all legal costs" if the petition is dismissed or if at trial, the jury finds for the defendant slaveholder. The legislature gave the court the authority to waive these costs if the court found there was "probable ground to suppose the said petitioner or petitioners had a right to freedom."

Enslaved plaintiffs in Washington, D.C., learned about attorneys through word of mouth and often based on their family's prior experience with freedom suits in Prince George's County. Francis Scott Key allegedly represented freedom petitioners pro bono, but there is no direct evidence of pro bono arrangements. The D.C. Court may also have assigned attorneys when plaintiffs did not already have representation.

There is evidence that enslaved plaintiffs in D.C. did, in fact, bear some of the costs and hire attorneys. Plaintiffs such as Daniel Bell and James Ash hired themselves out for work. They used their earned wages to bring cases on behalf of themselves and other family members, paying the court costs and other expenses necessary to initiate freedom suits.

How many freedom suits were successful?

Of the 140 freedom petitions heard before the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia where the outcome is known, just over half of them were decided in favor of freedom for the petitioners.