The Timing of Queen v. Hepburn: An exploration of African American Networks in the Early Republic

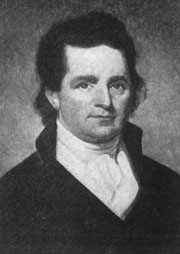

On January 8, 1810, Francis Scott Key was going to file some of the first petitions for freedom he had ever handled, one for Mina Queen and her daughter Louisa against the slaveholder John Hepburn, a second for Priscilla Queen against a Jesuit priest and slaveholder named Francis Neale, and a third for Hester Queen against slaveholders James Nevitt and Richard Nally.

The Queen v. Hepburn case would eventually go to the U. S. Supreme Court in 1813, and Chief Justice John Marshall's majority opinion would establish the "hearsay" rule in American jurisprudence. The decision was momentous because it rendered enslaved petitioners categorically as property before the law. And the 1813 decision meant that petitioners for freedom could not use hearsay testimony about the status of their ancestors. One door to freedom was closed decisively.1

Venues for Freedom

But on Monday, January 8, 1810 when Key filed the Queen cases, this outcome was far from determined. The Queen family had created a vibrant network of free and enslaved branches in Maryland, and in the 1790s, they had won a series of petition cases in Prince George's County and in the General Court of the Western Shore. Their success had prompted the Maryland General Assembly to revise its slave laws in 1796 in ways that made petitions for freedom much more difficult for the enslaved. The act required that petitions be heard in the local county courts rather than in the higher appellate General Court, making it more likely that white planters at the local level would serve on juries hearing these cases. The new law also required that plaintiff's attorneys bear the costs of the litigation if the case was decided for the defendant slaveholder. Scholars have suggested that these more restrictive acts in 1796 effectively blunted petitions for freedom in Maryland.

But in 1800, a new jurisdiction opened with the creation of a national capital city in Washington, D.C. The District of Columbia incorporated the law of Maryland on its Maryland side and the law of Virginia on its Virginia side. The D.C. Circuit Court was a federal bench, but acted both as a lower court and an appellate court. It therefore could serve as the court of original jurisdiction for petitions for freedom under the Maryland 1796 act that operated within the Maryland parts of the District.

With this alternative venue available, why did it take Mina Queen and the other Queens until January 8, 1810 to file petitions for freedom in the D.C. Circuit Court? And how did Francis ("Frank" as he was called) Scott Key come to represent the Queens in these cases?

Scholars have suggested that Key and other attorneys took such cases pro bono or as a duty to the court. In this view, the attorneys at the local bar rotated plaintiffs, had little regard for the particularities of their cases, and in general carried out the function of the law as court officers. Few studies have explored the ways that enslaved clients worked with attorneys. Most of the literature suggests that the cases came forward when they did for reasons peculiar to the individual litigants: the court assigned an attorney, an enslaved person coming of age, the death of a slaveholder, the possibility of being sold or another life-altering change.2

Enslaved black plaintiffs possessed a high degree of independent, political awareness and made decisions about the timing of their litigation based on a deep understanding of the familial, legal, and political networks around them.

This essay argues that enslaved black plaintiffs possessed a high degree of independent, political awareness and made decisions about the timing of their litigation based on a deep understanding of the familial, legal, and political networks around them. The timing of the Queen v. Hepburn case was neither accidental nor unimportant. It serves as a striking example of what James Scott has termed infrapolitics: "the strategic form that the resistance of subjects must assume under conditions of great peril . . . All political action takes forms that are designed to obscure their intentions or to take cover behind an apparent meaning." If we recognize that there was a "hidden transcript" to Queen v. Hepburn, that their resistance to enslavement was multi-generational and calibrated, it becomes possible to explain why the Queens filed their petitions when they did and why they chose Francis Scott Key as their attorney.3

The Queens of Maryland

Three related events came together in 1809 that provided the opportunity for the Queen family to begin a new round of petitions for freedom. First, the District of Columbia passed a "black code" in 1808, restricting the movement of free blacks, just as the slave trade to the cotton frontier began in earnest. In this setting, free blacks were required to register at court every year, and the Queens, like many other free and enslaved families, may have felt the effects of this greater scrutiny. As an earlier era of laxity in policing the status of free blacks gave way to an era of surveillance, these families took more aggressive measures to document their status. Since the 1790s, they had used petition cases to secure political and social standing in the community and organize and sustain family networks.4

Second, the prominent Prince George's County attorney and D.C. Circuit Court justice, Allen Bowie Duckett, died in 1809, opening the possibility for a change in the character of the Court. The Queens acted at this moment, not before. And third, the slaveholder and Jesuit priest Rev. Francis Neale assumed his new post as president of Georgetown College and moved to the District of Columbia, where the Queens might gain a more favorable hearing for their petitions than in Prince George's County or St. Mary's County, Maryland. As it turns out, Priscilla Queen's case against Neale, rather than Mina Queen's against John Hepburn, may have been the lead case that determined the timing of the litigation.

The number of free blacks in Maryland grew steadily between 1783 and 1810. The growing free black population, mostly liberated by petitions for freedom, offered a visible, meaningful, and stark contrast to racial slavery. In 1800, fifteen percent of all Maryland African Americans were free. By 1810 when the Queens filed their petitions for freedom, there were 33,927 free blacks living in Maryland, thirty percent of all Maryland African Americans. With one in every three blacks a free person, Maryland had become a strikingly different society after the Revolution.5

Enslaved people began bargaining with slaveholders at key moments: the death of a patriarch, a dip in the market, or the recognition—whether spoken or unspoken—of long and faithful service.

But these manumissions did not naturally flow from the idealism of the Revolution, religious awakening, or on account of declining tobacco prices. Instead, against the terrifying backdrop of interstate slave traders selling African Americans to the Mississippi cotton frontier, enslaved people began bargaining with slaveholders at key moments: the death of a patriarch, a dip in the market, or the recognition—whether spoken or unspoken—of long and faithful service. They used the law where and when they could, and in Maryland around 1810, the Queens had established themselves as a family of consequence, a family with an extended network that could, in all its branches, provide an avenue toward freedom. Rather than take their master's surnames, the Queens and other Maryland black families strategically protected their kin networks over the 18th century. In fact, between 1790 and 1840, no surname was more popular in Maryland than "Queen."6

One reason for the Queens's solidarity in these years had to do with the circumstances of their enslavement. Beginning in the late 1720s, they had been held as slaves primarily by Jesuit priests who managed multiple tobacco plantations in Maryland, most of them inherited from one of the wealthiest planters in eighteenth-century Maryland, James Carroll. After the American Revolution, some of the Queens, led by Edward 'Ned' Queen, obtained their freedom in the 1790s through petitions for freedom filed in the Maryland courts against one of the Jesuit priests, Rev. John Ashton. Philip Barton Key, Frank's uncle, and Gabriel Duvall, another Prince George's County attorney, represented Ned Queen. Petition cases were tried in the General Court of the Western Shore of Maryland, which had original jurisdiction over all petitions for freedom until 1796, when the law was changed to make petitions more difficult by requiring them to be tried in the county courts first. Ned Queen's case affected over twenty other Queen family members who had brought petitions against Ashton. Simon Queen secured his freedom in these years as well, and he was called to serve as a witness in both Priscilla Queen's and Mina Queen's 1810 case.7

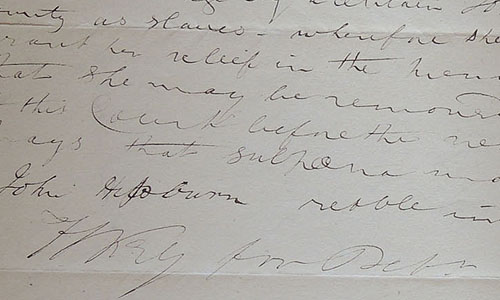

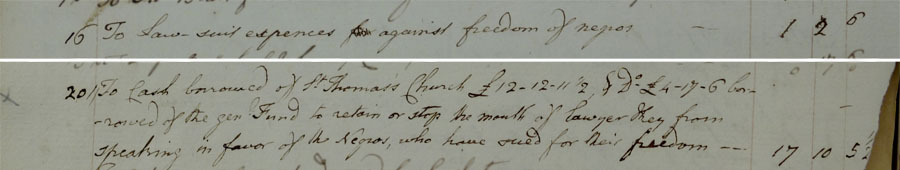

The account book for St. Thomas Manor included the following entry: "To . . . retain or stop the mouth of lawyer Key from speaking in favor of the Negroes who have sued for their freedom."

To deal with the situation and to prevent further petitions for freedom from their enslaved laborers, the Jesuits took quiet but decisive steps. Borrowing money from the general fund of one of their congregations, they paid Philip Barton Key to stop representing enslaved families on their plantations. Key had won the successful judgment for Ned Queen on May 23, 1794. Three months later in August, the account book for St. Thomas Manor included the following entry: "To . . . retain or stop the mouth of lawyer Key from speaking in favor of the Negroes who have sued for their freedom." He was paid £4 17s 6p, and although Key appears to have accepted the retainer, he continued to represent the Queens in twenty individual cases that he had filed in April 1794 in Prince George's County, all of them against Rev. John Ashton.8

Having prevented Key from representing more families, the Jesuits retained Allen Bowie Duckett to represent Ashton in these subsequent Queen cases. Key stayed on the docket representing the Queens along with his co-counsel Gabriel Duvall. All twenty Queens were freed in April 1796.

Richard Ridgely, one of the most distinguished Maryland attorneys of the day, argued in the 1799 jury trial: "slavery is incompatible with every principle of religion and morality. It is unnatural and contrary to the maxims of political law, more especially in this country, where 'we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.'"

Then in 1797, Charles Mahoney filed a similar petition for freedom case against Ashton in Prince George's County. This time, however, Philip Barton Key defended the slaveholding Jesuit. Meanwhile, some of the most talented lawyers in Maryland had lined up to argue the Mahoney case against Key. Some of them were Key's rivals for political office, including the upcoming 1800 election for the House of Delegates. Mahoney's attorney, Richard Ridgely, one of the most distinguished Maryland attorneys of the day, argued in the 1799 jury trial: "slavery is incompatible with every principle of religion and morality. It is unnatural and contrary to the maxims of political law, more especially in this country, where 'we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.'" Mahoney's other attorney, John Johnson, joined Ridgely in this argument, drew heavily on Enlightenment ideas about universal rights, and repeatedly cited Lord Mansfield's decision in the famous Somerset v. Stewart case. The jury granted Charles Mahoney his freedom, but the case was appealed and retried several times. As events in Saint-Domingue provoked greater and greater anxiety among slaveholding whites in Maryland, the Mahoney case lurched to a conclusion in 1802 with its third and final trial and a jury that decided Charles Mahoney was not free.9

The Politics of Freedom Seeking

Evidence indicates that these contests had immediate political significance, as African American men from these families began voting in state elections. In the years around 1800, petition cases in Maryland became a theater for acting out political allegiances. In 1796, Maryland had codified a distinction in voter eligibility between freeborn African Americans and freed or manumitted slaves, barring the latter from voting if they were manumitted after 1783. In the 1800 election for the Maryland House of Delegates, Philip Barton Key came in third behind John Johnson by sixteen votes, losing the seat. At least twenty black voters appeared at the polls, but four were disqualified on the grounds that they were not freeborn but had obtained their freedom in petition suits after 1783. Six voters overcame challenges to their eligibility. In all, sixteen black voters cast a ballot for John Johnson, while only five voted for Key. Key contested the election in the House arguing that some voters were ineligible and others who were barred were in fact eligible. He did not prevail, and Johnson was seated with Allen Quynn. In this close election, black voters included members of the Shorter, Joice, Queen, Mahoney, and Butler families. For several years before and after 1800, the Maryland House considered a proposal to drop the property qualification and restrict voting to white males over twenty-one, but the Senate persisted in keeping the property qualification. In 1802, resistance gave way and Maryland passed a state constitutional amendment limiting the vote to white men.10

Philp Barton Key's unpopularity with black voters, evident in the 1800 election for the Maryland House, stemmed in all likelihood from representing slaveholders in a series of petition cases, especially Rev. John Ashton. Key defended over twenty slaveholders in petition cases in Prince George's County between 1794 and 1796. And although he represented the Queens against Ashton in earlier cases, he defended Ashton in the Mahoney litigation.

With Key retained by the Jesuits, enslaved families had one fewer attorney willing to represent them. The Jesuits went further. They hired a prominent Prince George's County attorney, Allen Bowie Duckett, to represent them against the Queens. Then in 1801, Duckett became one of the first federal judges appointed to the D.C. Circuit Court by President Thomas Jefferson. As a result, even though the chief justice of the D.C. Court, William Cranch, was a Federalist appointee, the court included two slaveholders, Nicholas Fitzhugh from Virginia and Duckett from Maryland. Duckett's history with the Jesuits, his connections to Prince George's County, and his prominence may have warded off freedom petitions while he sat on the bench.11

Duckett's death in 1809 may have prompted the Queens to turn to Francis Scott Key. With their nemesis Duckett dead and their advocate Gabriel Duvall as a witness, it might have seemed an especially opportune moment for the Queen family to gain a favorable hearing. President James Madison filled Duckett's seat on the bench with the appointment of U.S. Senator Buckner Thruston, a Jeffersonian Republican from Kentucky who had done little to distinguish himself in the Senate during his five years in office. Thruston had been a law student of George Wythe at the College of William and Mary, whose emancipationist views on slavery were well known in the aftermath of the Revolution. Thruston's appointment on December 13, 1809 changed the character of the Court in petitions for freedom, especially those with their origins in Prince George's County, Maryland.

Finally, Philip Barton Key left Washington, D.C., in 1806 to run for office in Montgomery County, Maryland, where he was elected to Congress as a Federalist. Key's nephew, Francis Scott Key, took over some of his uncle's law practice in 1806. In 1809, Frank Key represented enslaved persons in three petitions for freedom. Like his uncle, he also represented a slaveholder. So, Key probably took on the Queens as his clients sometime in 1809 because his uncle had represented them. They probably turned to him because they knew that Philip Barton Key had continued to represent the Queens in 1796, even after his retainer by the Jesuits.

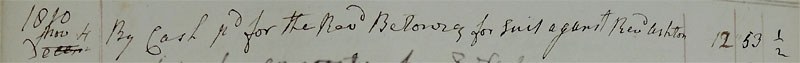

It is possible that Priscilla brought her case when she did because Rev. Francis Neale brought her to Georgetown and the move out of Maryland offered a change of venue: different jurors, different judges, and different possibilities. Born in 1764, the great-granddaughter of Mary Queen, Priscilla Queen was one of the last Queens still held by the Jesuits. As the oldest of the Queen women in these cases, Priscilla may have been the leader. They knew that their best case was one that pitted them against the Jesuits, because they could more easily establish the chain of testimony about Mary Queen and her descendants. Her case, after all, included the testimony of her uncle, Simon Queen, a free black man who had successfully obtained his freedom from Rev. John Ashton. The Jesuits continued to pay for lawyers to fight the Queen family's claim to freedom. On November 4, 1810, the St. Thomas' Manor accounts included an expense of $14.73 for "the Queen trial," presumably to defend Rev. Francis Neale against the claim made by Priscilla Queen.12

Strategies of Freedom Making

The courts were critical arenas of contestation over freedom and family relationships, the place where freedom was often given shape and definition in the flow of time and everyday life.

In a highly legalistic culture, like the newly formed United States and its predecessor English colonies, the courts were critical arenas of contestation over freedom and family relationships, the place where freedom was often given shape and definition in the flow of time and everyday life. Everyday conflicts were brought to court: a contract made and broken, an injury given, an insult hurled, a marriage unrecognized, a law or ordinance violated, a person's status challenged. And in the court, four types of actors came together whenever petitions for freedom were heard: enslaved and free blacks as plaintiffs, slaveholders as defendants, the attorneys representing the parties, and the judges. Witnesses gave testimony and shaped everyone's understanding of the family relationships at issue. The interaction among these parties after the Revolution is not very well understood and the records of their meetings have in some cases been lost. While some of the matters were appealed and somewhat more complete reports of the cases documented in appellate decisions, the vast majority of court cases ended in the district courts and their records remain spotty.13

Still, these case files give us clues to the process of claiming freedom and to one of the central sites for the making of freedom. In these records, even those with only one or two documents such as a summons or a petition, we find the names of lawyers, plaintiffs, defendants, and judges who worked out these claims, sometimes over successive generations. We also find the legal fictions they created. Historian Walter Johnson has suggested that legal records contain "stock figures" and court dockets should be read as "lies." He is certainly correct. Attorneys create fictions of a sort, a particular version of events, deeds, and personalities. Sworn testimonies corroborate and fill out these characters that appear in case after case: the inveterate gambler, the dissipated master, the trickster, the huckster, and the card sharp. What happened in the courtroom and in the attorney's offices sheds light on these fictions and exposes the many ways freedom was worked.14

Crucially, the procedural rules of the law in the early United States were unsettled and not at all uniform from court to court and jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Treatises began to regularize these rules, but judges and lawyers relied on sometimes starkly different approaches. Jury trials in particular were less common and thought to be less reliable. Judges allowed hearsay in some cases and not others. The inherited common law of English courts had distinctly American adaptations and improvisations. The creation of the United States came with further opportunities for innovation.15

Working toward freedom therefore necessarily involved many collaborators. At the least, an enslaved person needed an attorney to file a petition for freedom. We now know more about these cases, and in the last decade, historians have uncovered thousands of freedom suits in local courts before the Civil War.16 These cases featured complex networks of families, friends, associates, attorneys, and slaveholders. Legal actions created documentary records that linked generations across time, enfolding their histories into resources of resistance. They cannot be understood in isolation or as singular legal decisions. Instead, as in the case of Queen v. Hepburn, Priscilla and Mina Queen brought their petitions for freedom to the D.C. Circuit Court at a particular moment in time, not only summoning the defendant slaveholders to appear in court but also enlivening the historical, material, and familial networks maintained across three generations.

Endnotes

1. For one of the most detailed treatments of Queen v. Hepburn, see R. Kent. Newmeyer, John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2007), 441-442, 444-446. [back]

2. On lawyers, see Ted Maris-Wolf, "Black Clients, White Attorneys: Life, Liberty, and Law in Virginia Communities," a paper given at the American Society for Legal History Conference, St. Louis, October 2012. Also Maris-Wolf, "Liberty, Bondage, and the Pursuit of Happiness: The Free Black Expulsion Law and Self-Enslavement in Virginia, 1806-1864," (Ph.D. Dissertation, The College of William and Mary, 2011). On Washington, D.C., see Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003); Kathleen M. Lesko, Black Georgetown Remembered: A History of Its Black Community from the Founding of 'The Town of George' in 1751 to the Present Day (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1991); Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Jefferson Morely, Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key, and the Forgotten Race Riot of 1835 (New York: Nan A. Talese, 2012). [back]

3. On infrapolitics see James Scott, "Beyond the War of Words: Cautious Resistance and Calculated Conformity," and "The Infrapolitics of Subordinate Groups," in L. Amoore, ed. The Global Resistance Reader (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), 71; also Robin D. G. Kelley, Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class (New York: Free Press, 1994). [back]

4. On D.C. and black codes, Letitia Woods Brown, Free Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1790-1846 (New York, Oxford University Press, 1972), 10-11. Howard B. Furer, Washington, A Chronological and Documentary History, 1790-1970 (Oceana Publications), 67. Kenneth Winkle, Lincoln's Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, D.C. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013), 14. See Vernon Valentine Palmer, "The Customs of Slavery: The War Without Arms," American Journal of Legal History Vol. 48 No. 2 (April 2006), 177. Also J. D. Dickey, Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, D.C. (Lyons Press, 2014). [back]

5. See T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997). On the American Revolution as a "turning point" in judicial decision-making about freedom suits and slavery, see Jason A. Gillmer, "Suing for Freedom: Interracial Sex, Slave Law, and Racial Identity in the Post-Revolutionary and Antebellum South," 82 N.C. L. Rev. 535 2003-2004. [back]

6. From 1790 to 1840 the most popular surname of free black household heads in Maryland was Queen. John Joseph Condon, "Manumission, Slavery, and Family in Post Revolutionary Rural Chesapeake: Ann Arundel County, Maryland," (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 2001), 211 see footnote 370. [back]

7. Eric Papenfuse, "From Recompense to Revolution: Mahoney v. Ashton and the Transfiguration of Maryland Culture, 1791-1802," Slavery and Abolition Vol. 15, #3, Dec 1994, p. 52. [back]

8. St. Thomas Manor Account Book 1793-1825 Box 46, Folder 2, Maryland Province Archives, Society of Jesus, Georgetown University Manuscripts. June 16, 1794, August 20, 1794, January 28, 1803, and November 4, 1810. [back]

9. Eric Papenfuse, "From Recompense to Revolution: Mahoney v. Ashton and the Transfiguration of Maryland Culture, 1791-1802," 44. [back]

10. David S. Bogen, "The Annapolis Poll Books of 1800 and 1804: African American Voting in the Early Republic," Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. 86 No. 1 (Spring 1991), 57-65. [back]

11. On the appointment of Duckett, see Executive Journal, First Session, 9th Congress, p. 25. Senate Executive Proceedings, Vol. 2, December 11, 1805. [back]

12. St. Thomas Manor Account Book 1793-1825 Box 46, Folder 2, Maryland Province Archives, Society of Jesus, Georgetown University Manuscripts. November 4, 1810. [back]

13. For the emphasis on the flow of time, I am influenced by Christopher Tomlins, "Historicism and Materiality in Legal Theory," a paper given at the American Historical Association Conference, January 2015. Tomlins emphasizes "the object is not enlivened by the relationalities of its time, within which it allegedly belongs, but by the fold of time that creates it in constellation with the present, the moment of its recognition." For one of the best account of legal documentation and its significances across time and space in the nineteenth century, see Rebecca J. Scott and Jean M. Hebrard, Freedom Papers: An Atlantic Odyssey in the Age of Emancipation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012). [back]

14. Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 12. [back]

15. The literature on procedure is large; the key recent work is Laura Edwards, The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). [back]

16. On freedom petitions in St. Louis, Missouri, see Lea Vandervelde, Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom before Dred Scott (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014). See also Anne Silverwood Twitty, "Slavery and Freedom in the American Confluence, from the Northwest Ordinance to Dred Scott," (Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 2010). [back]