"She's been her own mistress...": The Long History of Charlotte Dupee v. Henry Clay, 1790-1840.

As Washington, D.C., thawed out in February of 1829, Congress convened inside the United States Capitol to count the votes for President of the United States. After each state's packet containing their vote was unsealed and reviewed, it was revealed that after an acrimonious campaign, Andrew Jackson had defeated the incumbent John Quincy Adams.1

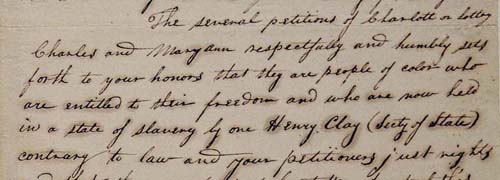

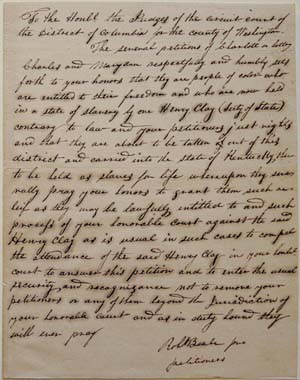

Henry Clay, the veteran Kentucky politician and Quincy Adams' Secretary of State, and those he enslaved were particularly affected. In order to make way for the incoming administration, Clay made plans to vacate his post in Washington and return to Ashland, his Kentucky plantation. But before the outgoing Clay could digest the results of the election, he received a shocking notice. Claiming that she was born of a free woman and wrongfully enslaved, Charlotte Dupee, a woman enslaved by Henry Clay for twenty-three years, was suing the powerful statesmen for her freedom.2

Timing was the linchpin of Charlotte Dupee's freedom suit. She purposefully filed her petition against Clay in Washington, D.C., before his return to Kentucky. Doing so enabled Dupee and her lawyer to take advantage of favorable freedom suit legal precedents in the jurisdiction. Moreover, Dupee knew she would be mandated by law to remain in the District during the litigation of her case and, crucially, while Clay returned to his plantation in Kentucky. As a result, Charlotte Dupee exercised a unique degree of freedom in Washington, D.C. – and even worked for wages – while her slaveholder returned to Kentucky.

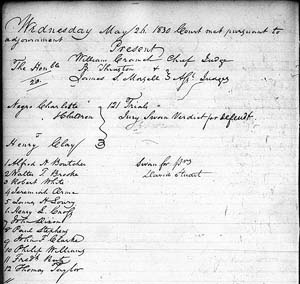

In May 1830, the court ruled against Charlotte Dupee; her formal petition for freedom was denied. But, while pivotal, this eighteen-month-long episode in Charlotte Dupee's life is only a snapshot of her long personal struggle for freedom. Prior research conveys Dupee's freedom suit as a blip in the biography of Henry Clay. Reflecting the lack of research into Dupee's entire life, resources that focus on slavery or freedom suits in Washington, D.C., only devote a sentence or two to Dupee's suit. As a result, vital moments in Charlotte Dupee's life that directly informed her freedom suit's argument and strategy are absent from historical studies. Beginning with what was likely her first brutal encounter with the system of slavery at five years old and continuing through her eventual emancipation, this essay will replace Henry Clay with Charlotte Dupee at the forefront of her own history.3

Vital moments in Charlotte Dupee's life that directly informed her freedom suit's argument and strategy are absent from historical studies.

"...forever set free": Charlotte Dupee's Early Exposures to Freedom

Charlotte Dupee was born during a period of immense change and uncertainty – especially for enslaved persons. In 1787, the year of Dupee's birth, the Founders deliberated slavery's constitutional role in the new Republic. Maryland abolitionists capitalized on these debates to highlight the paradox of slavery and liberty in the new United States. Amid this discourse, the institution of slavery in Maryland underwent an economic change. The tobacco-based economy on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake increased the demand for slaves in areas like Joppa Town, Annapolis, and Port Tobacco. Across the Chesapeake Bay, however, a grain-based economy gained a foothold and resulted in decreased demand for labor on the Eastern Shore. It was on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, in Dorchester County, where Charlotte Dupee was born.4

Dupee's immediate and extended family, the Standleys, were long-time residents of the Eastern Shore. Exploiting gaps between the economic and cultural shifts occurring, the Standleys were also veterans of alternative pathways to freedom. One commonly used strategy was purchased familial manumission. This long and precarious process began with free family members budgeting and accumulating wealth through wages. When enough earnings were saved – possibly months or years into the process – they purchased the freedom of their family members from their enslaver. Should the process be successful and freedom obtained, the free family would begin the process anew.5

But not all purchased familial manumissions were successful. Ostensibly a few simple steps, the journey was arduous and fraught with uncertainty. Foremost among the pitfalls for enslaved persons was the imbalance of bargaining power between the enslaver and their chattel. At any point in the process, slaveholders could change their terms, increase the price of their property, or call off the transaction entirely. Despite these obstacles, purchased familial manumission remained a viable alternative pathway to freedom for enslaved persons on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in early America. In fact, Charlotte Dupee's father chose that path when Dupee was five-years old.6

Purchased familial manumission remained a viable alternative pathway to freedom for enslaved persons on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in early America.

Dupee's father, George Standley, was a free man by 1790. While it is unknown how Standley came to be free, the census record identifies him under the category "free negroes and mulatto." Directly above George Standley was one of the largest slaveholders in Dorchester County.7

Daniel Parker owned 20 humans in 1790. Four of the twenty individuals under Parker's bondage included George Standley's wife, Rachel, and Standley's three children: Jonathan, Leah, and Charlotte. The indent at which George Standley's name appears under Daniel Parker's in the 1790 census indicates that Standley himself may have been enslaved under Daniel Parker at one time and now worked for him. Was Standley voluntarily manumitted by Parker? Did Standley purchase his own freedom? Or was Standley another link in the long lineage of Standleys pursuing purchased familial manumission?8

The answer to these questions remains uncertain. However, two years after Charlotte Dupee's father was listed as a free man in the 1790 census, Standley tapped into the network of knowledge sewn by his ancestors and attempted to purchase the freedom of his family.

After accumulating his earnings, George Standley acquired his enslaved wife, Rachel, and two of his three children, Leah and Jonathan, from Daniel Parker. Then, "thinking it to be [his] indispensable duty to free them," Standley manumitted Rachel and, on a conditional basis, Leah and Jonathan. Charlotte was not manumitted that day. Instead, she remained enslaved by Daniel Parker for another five years.9

It is difficult to discern why Dupee was not included in the arrangement. Perhaps with one eye on the abolition of the international slave trade, Parker wanted to hold on to the five-year-old girl's future reproductive capacity to supplement his personal slave holdings. Maybe George Standley failed to accumulate enough wealth to purchase the freedom of his entire family, and Charlotte was a victim of the chattel principle. Regardless, the result remained the same. Charlotte Dupee witnessed freedom the day her father purchased and manumitted her siblings and mother. But that sacred human right eluded her. At a young age, Charlotte Dupee learned that her freedom, and her body, had a price.10

"I likewise warrant her to be sound": 600 Miles to Kentucky, 1792-1806

Charlotte Dupee remained enslaved by Daniel Parker for approximately three more years after her father's strategy of purchased familial manumission in 1792. Before Parker's death near the turn of the century, he sold Dupee to a tailor in Dorchester County named James Condon. Condon, a formerly non-slave owning tailor, possessed his own economic and social aspirations. He viewed his purchasing the female body of a teenage Charlotte Dupee in a similar light as so many members of the Southern laboring class: an expedient step to becoming a Southern patriarch. "The market in slaves held the promise that nonslaveholders could buy their way into the master class," and Condon pursued that promise when he purchased Dupee. By purchasing her for "a price at that time considered high," Condon staked his claim in the world of powerful white men. It was an objective that eventually led him – and Charlotte – to Lexington, Kentucky.11

Around the time Condon entered Dupee's life, an array of people lived at the tailor's Cambridge, Maryland, residence. According to the 1800 Dorchester County census, Condon's household included at least five sons, one daughter, and his wife. Two "free white males" aged between 16-25 were also incorporated into the Condon ménage – likely John Mowbray and William Flint. These two apprentices later contributed an illuminating 1829 testimony as part of Dupee's freedom suit that provided a rare insight into Charlotte Dupee's life under Condon's ownership. First, when Condon purchased Dupee at thirteen years old, she was Condon's only slave. Second, the testimony suggests that Dupee likely worked as a domestic servant and nursed the Condon children. Dupee would be commanded to conduct these domestic chores for the entirety of her enslaved life.12

Outside of these glimpses in testimonies, there is no known evidence of Dupee's everyday life while enslaved by Condon. But within that testimony, John Mowbray's recollection of life in the Condon household proves most pertinent to Dupee's later claim to freedom. When asked by interrogators whether he had any knowledge that might aid in Dupee's argument for freedom, Mowbary made an interesting admission. "While in Condon's family I have frequently heard Mrs: Condon say, at times when a little provoked with Lotty's conduct," Mowbary began, "that she (Lotty) should not be free so soon as Lotty expected." The apprentice then continued, "I have also heard in Condons family that Lotty was promised her freedom; whether by James Condon, his wife, or Daniel Parker I do not know."13

The unmanifested promise of freedom served as a major pillar of Dupee's later freedom suit. Mowbary's testimony suggests that such a promise could have been made; however, it was never put into writing and rather used as a threat. Still, the words, "should not be free so soon as Lotty expected" rings with suspicion. Even if hurled at Dupee in anger, such language from a slaveholder points to a promise of freedom being made to Dupee by a Condon at some point during Dupee's life at Condon's house. Because this argument is not substantiated by written evidence, we can only speculate about the promise actually occurring.

Outside of her duties, however, it is important to note that despite changing slaveholders, Dupee did not change location. She remained in Dorchester County, Maryland, where, as a result of George Standley's purchased familial manumission in 1792, Dupee's social network now definitely included free blacks. Dupee may have been able to communicate, in some capacity, with the kin network that served as models of freedom for generations.14

Extracted from a vital network of free and enslaved family members, Dupee held tightly onto the knowledge her kin had taught her about freedom, and eventually repackaged it to suit an altogether new environment of slavery.

The possibility of tapping into Charlotte Dupee's knowledgeable kin network lasted only five years into the new century. In the spring of 1805, James Condon ripped Dupee from her home, her family, and her kin network in Maryland and forcibly transported her hundreds of miles west to Lexington, Kentucky. Extracted from a vital network of free and enslaved family members, Dupee held tightly onto the knowledge her kin had taught her about freedom, and eventually repackaged it to suit an altogether new environment of slavery.

Upon settling in the western border state, Condon established his tailoring business in downtown Lexington and announced his presence to its citizens. But he did not stay static for long. Barely one year into his Lexington residency, Condon placed his old property on the market. His new location, a "small, red house, on Main Street," may have been in the shadow of one of Lexington's slave pens. His craving for membership in the Southern master class not yet satisfied, Condon decided to liquidate his valuable asset. In March of 1806, Condon sold Charlotte Dupee for "a very high price" to an up-and-coming politician named Henry Clay.15

Enslavement by Henry Clay meant Dupee was not owned by a mobility-seeking tailor anymore; she was the slave of a rising political figure.16

She Transformed Space: Decatur House, 1827-1830

Perhaps the most crucial relocation for Charlotte Dupee was her transition into Decatur House in the spring of 1827. Here, in the shadow of the White House, Dupee became more simultaneously interconnected with Washington's three main populations – white, free black, enslaved – than at any other time in her life. She also arrived in a city heated with political debate. "Perhaps no half decade in American history witnessed as many dizzying shifts in sectional political power as the years between 1827 and 1833," Robert Forbes observed. Much of this political power centered around the topic of slavery; and Henry Clay was often at the heart of the debates.17

At Decatur House, she was a domestic servant to whites, walked the city's streets among free blacks, and worked and lived with enslaved blacks in the rear quarters of the house. Dupee's presence in these environments, the conversations heard and had, and events observed and engaged with make her time in Decatur House truly influential in her quest for freedom.

Charlotte Dupee moved into Decatur House in 1827, one of Lafayette Park's most lustrous gems. The mansion underwent an important renovation in 1820 when a servants quarters was added to its rear. Stretching nearly one-half block from Decatur House to 17th street, with a north side facing a bustling H Street, pedestrians grazed the addition's long, yellow stucco walls on their way to the White House. But the structure's spatial status changed in 1827 when Charlotte Dupee became the first documented enslaved person to live in the quarters.18

While Charlotte Dupee was not free during this time, she likely engaged with free domestic servants at markets or on the street, communicated with enslaved workers in her quarters or at work sites, and overheard conversations of influential whites dining at Decatur House.

Dupee interacted with powerful white socialites and politicians, free blacks, and slaves while living at Decatur House. Elite white Washingtonians traversed the formal rooms of Decatur House, free black messengers ran errands from St. John's Parish across the District, and enslaved people labored to build the identity of Lafayette Square. While Charlotte Dupee was not free during this time, she likely engaged with free domestic servants at markets or on the street, communicated with enslaved workers in her quarters or at work sites, and overheard conversations of influential whites dining at Decatur House. Ideas and models of freedom abounded for Charlotte.19

While this network between whites, free blacks, and the enslaved developed, Henry Clay tried to navigate issues of slavery on his journey to summitting American politics. Vacillating between believing that slavery is a "necessary evil," the idea of gradual abolition, and even forced colonization of blacks in West Africa, Clay's own actions defined his stance on slavery less than one year before Charlotte sued for her freedom.20

A memorial advocating for the gradual abolition of slavery in the District was presented to the House of Representatives and the Senate in March 1828. Henry Clay was not one of the nearly 1,000 signatories who declared slavery not a "necessary evil," but "an evil of serious magnitude." However, many of his influential Washington peers did sign: at least three judges of the D.C. Circuit Court (most notably Chief Judge William Cranch) and future lawyer of Charlotte Dupee, Robert Beale.21

To Charlotte the paradox was evident: while politicians attempted to scrub away the stain of slavery from Washington's palaces of liberty, the insidious practice persisted. And she would likely persist as a cog in the American slave empire unless she acted. With the memorial handed to Congress and the debate over slavery in the District raging, Charlotte Dupee plotted her suit.

* * *

Equipped with a lifetime of interactions with freedom – from Maryland to Kentucky to Washington, D.C. – Charlotte Dupee filed her suit on February 13, 1829. With the assistance of her lawyer, Robert Beale, she based her case upon two main premises: that she was born of a free mother, and that her former enslaver, James Condon, promised Dupee her freedom on a conditional basis, which she alleged to have met. But timing was now of the essence. 22

John Quincy Adams' failed bid for the presidency, and Andrew Jackson's "mortifying" election, ignited Dupee's campaign. With Clay customarily resigning as Secretary of State and prepared to return to Kentucky, Dupee had to act quickly. If she decided to act while Clay was still Washington, he might stymie her efforts. If Dupee waited too long, she could be taken back to Kentucky, restricted by more stringent slave laws, and lose her opportunity to sue for her freedom all together. As Dupee would have known, D.C. law mandated that the petitioner stay within the boundaries of the District while the case was tried. By choosing to sue for her freedom mere weeks before he left the city, Charlotte was able to stay in the District and maintain a unique degree of independence from her enslaver. While Clay returned home to Kentucky to await the trial's outcome with her husband and two children, Dupee stayed at Decatur House, earning her own wages working for the new Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren.23

Archival evidence does not describe the detailed minutes of Charlotte Dupee's trial. But remarkable letters that Clay wrote around the trial reveal the broad impact of Dupee's suit. Though Clay claimed he knew nothing of Dupee's intention to file for her freedom, the mere optic of the suit provoked a strong rejoinder. After he received a summons from the Circuit Court, Clay immediately penned a response defending his honor and character. Justifying the legality of his 1806 purchase and ownership of Dupee, Clay explicitly denied "that the petitioners...have any right, or just claim whatever, to their freedom." Clay proceeded to lay out his argument in chronological order in a tone typical of the self-perceived role as a benevolent slave master. After all, Clay contended, he was the one who allowed Dupee to visit her family on the Eastern Shore once in 1816 and again the summer before 1829. To Clay, the only impetus behind this suit was a cynical one; it had to be the work of his Jacksonian political enemies.24

Clay was not alone in this theory. There is no documentation of agreed conditional manumission between Charlotte and her second owner, James Condon, which makes this basis of Dupee's case a fragile one. But Henry Clay still needed assurance from James Condon to calm his nerves. After writing a letter to Condon inquiring about whether a promise of freedom was ever made to Dupee, Condon replied in a manner similar to Clay's: a gentleman concerned for his own character, honor, and standing. In the intervening years between his sale of Dupee and Clay's concerning note, Condon served a one-year term as mayor of Nashville, Tennessee – achieving the social mobility he set out from Maryland in search for when Dupee was a teenager. Intentionally or not, Charlotte Dupee's freedom petition extended beyond her freedom: it jeopardized the slaveholding reputations of both Clay and Condon.25

Intentionally or not, Charlotte Dupee's freedom petition extended beyond her freedom: it jeopardized the slaveholding reputations of both Clay and Condon.

In his opening paragraphs, Condon accused Dupee of descending into "moral turpitude," then proceeded to assume a defensive position. Condon interestingly described himself as a vulnerable elderly man who would never think of illegally practicing slavery, especially in a transaction with a man of Henry Clay's stature. "The foregoing charge," Condon wrote to the statesman, "would certainly be exceedingly painful to the feelings of an old Man [sic], who has pass[e]d a life of more than 60 years without ever having been call[e]d upon to answer before the Court of Justice, or any other earthly Tribunal for any Crime wat-ever [sic]." After an allegedly unsullied slaveholding record, Condon portrayed himself as a victim. He then proceeded to describe his own "recollection of the facts" which were "as clear in [his] mind as if they had transpired yesterday."26

Condon's private testimony to Clay does not differ from the answers he gave to interrogators later in the summer. He rightly pointed out that Charlotte's mother was free. However, she had obtained her freedom in 1792 – five years after Charlotte's birth. Later, Condon asserted that he paid "a very high price" for Dupee around 1795. Immediately after his arrival in Kentucky a decade later, Condon contended that he lawfully registered Dupee as his slave. Although the interrogators later questioned his motives for leaving Maryland, Condon maintained that if he had transported Charlotte illegally out of Maryland, the "strict & rigid regulations of the Abolition Society" would have caught him in the act. He made no mention of Dupee's conditional manumission – verbal or otherwise. Instead, Condon repeatedly defended his prior ownership of Dupee, proclaimed he followed the rules of slavery, and assured Clay that Charlotte had no claim to freedom whatsoever. Like his fellow slaveholder, Condon confidently believed that Charlotte was a pawn deployed by Clay's political enemies with slanderous aims.27

That is, until Condon completed two-thirds of his letter. After spending the majority of the correspondence defending himself and his character, Condon divulged to Clay one "reflection [that] has occur[re]d to my mind & perhaps it may have had some influence upon her [Charlotte Dupee's] mind." He admitted that he might have promised Dupee her freedom long ago. But this was "predicated upon the Condition of long & faithful services" by her unto Condon. When testimony was collected, interrogations of Condon's apprentices in Maryland addressed this same question, but their fingers pointed towards Mrs. Condon. John Mowbray, who moved into the Condon's household after Charlotte, testified that "while in Condon's family I...frequently heard Mrs: Condon say, at times when a little provoked with Lotty's conduct, that she (Lotty) should not be free so soon as Lotty expected. I have also heard in Condons family that Lotty was promised her freedom; whether by James Condon, his wife, or Daniel Parker I do not know." Whether it was James Condon or his wife, a verbal promise of freedom seems to have been made to Charlotte Dupee sometime between the mid-1790s and 1806.28

Admissions like these worried Clay. Quick to recover, Condon shifted the blame from himself and his wife to Charlotte Dupee. No matter what promise was allegedly made, he argued, it was void by the time she filed for her freedom. According to Condon's reasoning, Charlotte violated any promise when she married Clay's Ashland manservant, Aaron Dupee, which some historians believe led to her sale to the then-senator. In Condon's view, she had not kept her promise of "long & faithful" service. Despite his concessions, Condon assured, Clay had nothing to worry about.29

The lack of written documentation further comforted Clay, who now rested at Ashland several hundred miles away from Charlotte. Without an extant document that stated that a promise of freedom was made by Condon, Charlotte Dupee's claim was essentially rendered as hearsay. It did not meet the evidentiary standard of the court raised by previous freedom suits in the District. One of her main arguments for freedom crumbled.30

As he prepared for his next presidential campaign, Clay privately "waited with some anxiety" for a resolution to Dupee's freedom suit. Finally, in May 1830, over one year since she filed, Charlotte Dupee discovered that her petition for freedom fell short. As a result, her legal protection in Washington, D.C., ceased. Nevertheless, she found new ways of resisting.31

Dupee exacerbated Clay's anxiety when she boldly refused to return to Ashland after her suit failed. Unable to persuade her to come back, Clay angrily ordered his administrator in the city, Philip Fendall, to imprison Dupee for her "perverse or refractory disposition:"32

"Her husband and children are here. Her refusal therefore to return home, when requested by me to do so through you, was unnatural towards them as it was disobedient to me. She has been her own mistress, upwards of 18 months, since I left her at Washington, in consequence of the groundless writ which she was prompted to bring against me for her freedom; and as that writ has been decided against her, and as her conduct has created insubordination among her relatives here, I think it high time to put a stop to it..."33

The exposure of Clay's anxiety, anger, and personal perspective is almost unprecedented in the realm of slaveholder correspondence. Through the eyes of her owner, Charlotte Dupee broke every unwritten rule of the master-slave relationship by being "her own mistress" for eighteen months. First, he explicitly indicates his view that by staying in Washington, D.C., after the case was decided, Dupee behaved "unnaturally" toward her family. With children and a husband at Ashland, Clay demanded that she resume her "natural" role as mother, caregiver, and wife. Additionally, her refusal to return coupled with the vacancy at Ashland of a domestic servant marked blatant disobedience in the master's view. But Charlotte Dupee could not have been her own mistress without first being aware of when to file her freedom suit.

Clay's letter exposes the essence of Dupee's timing once again. By staying in Washington, Dupee was able to exercise a degree of freedom that would not have been possible had she filed her suit in, for example, 1827. Although she could not fully escape her omnipresent enslaved condition, the absence of restrictive labor and "natural" roles that accompanied her master's presence afforded Charlotte a kind of flexibility that allowed her to focus on her freedom suit. In other terms, her enslaved condition, and as a mother and a wife, combined with the shadow of Henry Clay would have hampered her ability to effectively file for her freedom at an earlier date.

Dupee's timing also counters the claims made by James Condon – and the Henry Clay biographers after him – that she was an instrument of subversion against Clay employed by political rivals. By the time Charlotte Dupee filed for her freedom, the vitriolic election of 1828 had ended. Andrew Jackson, Clay's main political foe, won. Libelous campaigns against Clay and President John Quincy Adams filled the newspapers of the preceding four years, and likely helped Jackson reach the White House. One biographer does note an earlier occasion where Jacksonians accused Clay of illegally holding a free slave in bondage in 1828; however, Clay responded to this foggy accusation by claiming he would honor the conditional freedom set by slave's prior owner.34

Claims of Charlotte Dupee being a political pawn remain unfounded. Instead, Dupee dictated the timing of her suit, not Clay or Jackson, because she possessed a lifetime of experience as an enslaved person familiar with strategies and pathways to freedom.

Accusation aside, with the inauguration a few weeks away from Charlotte's filing date, why would Jackson's camp bother to attack Clay after the election had already been decided? If such a tactic were to be used by Jackson's allies, they likely would have assisted Dupee earlier during the 1828 presidential campaign or waited for Henry Clay to run for president a few cycles later. Claims of Charlotte Dupee being a political pawn remain unfounded. Instead, Dupee dictated the timing of her suit, not Clay or Jackson, because she possessed a lifetime of experience as an enslaved person familiar with strategies and pathways to freedom.

And what result did her degree of independence yield? Strikingly, Clay admitted that Charlotte Dupee's actions "created insubordination among her relatives" at Ashland. Although unable to obtain her immediate manumission, Dupee exhibited a model of expressed freedom for her enslaved community in Kentucky. This, perhaps, is the most emphatic repercussion of Dupee's freedom suit. To be sure, Charlotte Dupee jarred Henry Clay and James Condon to such a degree that they exposed their fears in private correspondence. But her ability to incite "insubordination" among a slave community over 500 miles away from Washington, D.C., signifies the magnitude of her actions in 1829.35

"...she is the best creature I ever saw...": The Long 500-Miles Back to Kentucky

In September 1830, Henry Clay proclaimed that it was "high time to put a stop" to Charlotte Dupee's independence in Washington, D.C. He enlisted his administrator to arrange for Dupee to be jailed somewhere in the District. While records of her imprisonment remain undiscovered, the reason she was detained is certain: Dupee flouted the commands of her enslaver. Clay and Fendall scrounged Washington for a slave trader or a ship that could transport the defiant Dupee back to Kentucky or possibly to Clay's daughter in New Orleans. The prison served as a holding site for Dupee while Clay and Fendall straightened out the logistics. Eventually, the pair settled on the latter option. They dispatched Dupee via boat around the southeastern coast of the Atlantic, through the Gulf of Mexico, and into port at New Orleans. There, she found herself living in yet another culturally unique institution of slavery.36

New Orleans in the 1830s usually meant nightmarish prospects for slaves. But for Charlotte Dupee, it wasn't the slave market that awaited her in Louisiana, but a branch of Henry Clay's own plantation system. Dupee assumed the same role in New Orleans for Clay's daughter Anne Brown Clay Erwin as she executed at Ashland. It seems that as long as there were smaller children in the Clay family that needed a maternal "mammy" figure, "Aunt Lotty" was their caregiver. "Little Lucretia," Anne Brown Clay Erwin wrote of her daughter in an 1832 letter to Henry Clay, "is the most mischievous child of her age I ever saw." She continued, "Aunt Lotty and her have at least a dozen quarrels of a day; I cannot thank my dear Mother enough for having spared Lotty to me, she is the best creature I ever saw and appears to be quite as much attached to the children as she ever was to yours. Tell Mama I shall certainly execute her commission with a great deal of pleasure..."37

After caring for the Erwin children, Dupee eventually made her way back to Ashland under the supervision of Clay. It was there, on October 12, 1840, that he manumitted Dupee and her daughter, Mary Ann, effective immediately, "in Consideration of the long and faithful Service of my slave Charlotte and of her having nursed most of my children, and several of my grand Children." "But," the deed continued, "this deed is not Construed to Emancipate any of the Children of the said Charlotte and Mary Anne or either of them born prior to the execution thereof, the said Children so born before the present date remaining subject to me."38

Over one decade after she filed her freedom petition, repercussions of Charlotte Dupee's suit reverberated in the deed that ultimately manumitted her. According to the deed, all of the children born of Charlotte Dupee or Mary Ann prior to the manumission date remained his property or "subject" to him. By adding this clause at the end, he put in writing what Condon's and Clay's previous bills of sale lacked: explicit language documenting who was born of whom and the exact status of the mother's freedom. Charlotte Dupee administered Henry Clay an embarrassing lesson in 1829; in 1840, he committed himself to never repeating it again.

It is clear that Charlotte Dupee did more than challenge Clay's character and honor. When she refused to return to Kentucky, she defied nature, in the eyes of Clay, by being separated from her children and husband. Additionally, by her very actions, Charlotte incited sentiments of unrest among the Ashland slaves some 500 miles away from Washington, D.C.. For over a year between February 1829 and May 1830, Charlotte was, indeed, "her own mistress." Clay's tone was entirely condescending, but the comment hinted at a deeper truth. Determined to become free, Charlotte fashioned a period of temporary independence for herself. In a very real way, Charlotte became a living example of freedom for the enslaved at Ashland. Her actions exposed the lie of Clay's paternalism and exhibited an attainable pathway to freedom for those in her social network and for those who followed in her footsteps.

Endnotes

1. "The Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies." Accessed October 3, 2019. "Counting of Electoral Votes." In A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875, Register of Debates, 2nd Session., 20th Congress, House of Representatives. Gales & Seaton's Register, 1829: 350–51; "1828: The American Presidency Project." Accessed October 3, 2019. [back]

2. The Family Papers of Henry Clay, Vol XIV, 24 Nov. 1828 - 14 March 1829, Microfilm: Reel 3: Letter from Nathaniel Williams to Henry Clay, 24 Feb. 1829, Letter and invitation for Clay to party at Mansion Hotel, 06 March 1829, 16 March-11 Nov. 1829, Microfilm: Reel 3.; Thomas, 7-8, 16, 21, 76.; "Charlotte v. Henry Clay. Summons of Henry Clay," 13 Feb. 1829; Charlotte, Petition for Freedom, to the Judges of the Circuit Court of D.C. from Robert Beale, 18 Feb. 1829; Henry Clay to John Quincy Adams, resigning position of Secretary of State, 03 March 1829, The Papers of Henry Clay, ed. Robert Seager II, (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1984), 7:633. [back]

3. See "Slavery in the President's Neighborhood," and "Historic Decatur House," White House Historical Association. Apple, Lindsey. The Family Legacy of Henry Clay: In the Shadow of a Kentucky Patriarch (Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 2011), 80. David S. Heidler, and Jeanne T. Heidler. Henry Clay: The Essential American. New York, NY: Random House, Inc., 2010. [back]

4. Kenneth L. Carroll "Maryland Quakers and Slavery" Quaker History 72, no. 1 (1983): 31; Mary Beth Corrigan, "The Ties That Bind: The Pursuit of Community and Freedom Among Slaves and Free Blacks in the District of Columbia, 1800-1860," in Southern City, National Ambition: The Growth of Early Washington, D.C., 1800-1860, Octagon Research Series (George Washington University Center for Washington Area Studies, 1995), 71.; T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1997, pp. 3-5, 119, 123. [back]

5. Whitman, 3-5; Dorchester County Court, Certificates of Freedom, 1806-1851, Maryland State Archives, c689-1, Entry 2, p. 83. A Dorchester County Court levy book indicated on 15 May 1832 that 24-year old Harriet Jenkins was born to the free woman, Leah Stanley. The entry noted that Leah Stanley was "manumitted by George Stanley." The entry further describes Harriet Jenkins as 5'2.5" in height, dark chestnut skin, and "inclined to be fat", Dorchester County Court, Certificates of Freedom, 1806-1851, Maryland State Archives, c689-1, Entry 9. p. 9, Entry 1, 2, 7, 8. p.135-136; "Chattels," Legacy of Slavery in Maryland, Maryland State Archives; "United States Census, 1790," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 2 April 2019), George Standley, Dorchester, Maryland, United States; citing p. 433, NARA microfilm publication M637, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 3; FHL microfilm 568,143. Robert Standley, p. 423; Alise Standley, p. 429; Ezekiel Standley, p. 433; James Standley, p. 206; Sladdy Standley, p. 439. [back]

6. Whitman, 119, 129. [back]

7. "United States Census, 1790," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 2 April 2019), George Standley, Dorchester, Maryland, United States; citing p. 433, NARA microfilm publication M637, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 3. [back]

8. Ibid. [back]

9. Deed of Manumission (Copy?), George Standley of "Negro Rachel and others," 25 Feb. 1792. [back]

10. Whitman, 119, 129; Jennifer L. Morgan, "'Women's Sweat': Gender and Agricultural Labor in the Atlantic World," in Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).; Walter Johnson, "Reading Bodies and Marking Race" in Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), especially 113, 143-145. [back]

11. Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 Mary 1829, HCP, 7:630-31; Answers to Interrogatories of William Reed, 06 Nov. 1829; Walter Johnson. Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999, pp. 78-83, 198-200. W. Caleb McDaniel. Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019, pp. 103-105. [back]

12. "United States Census, 1800," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 4 April 2019), James Condon, Dorchester, Maryland, United States; citing p. 657, NARA microfilm publication M32, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 11; FHL microfilm 193,664; Answers to Interrogatories of Ezekiel Richardson et al., 06 Nov. 1829. [back]

13. Answers to Interrogatories of Ezekiel Richardson et al., 06 Nov. 1829. [back]

14. "United States Census, 1800," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 4 April 2019), George Negro, Dorchester, Maryland, United States; citing p. 650 and 657, NARA microfilm publication M32, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 11; FHL microfilm 193,664.; "United States Census, 1800," database with images, FamilySearch (accessed 4 April 2019), George Negro, Rachl Standley, Dorchester, Maryland, United States; citing p. 666 and 725, NARA microfilm publication M32, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 11; FHL microfilm 193,664. [back]

15. Answers to Interrogatories of William Flint, et al., 06 Nov. 1829; "JAMES CONDON, tailor," Kentucky Gazette and General Advertiser, classified, 25 June 1805. "REMOVAL, James Condon, tailor," dated 03 March 1806, Kentucky Gazette and General Advertiser, 20 May 1806; Answers to Interrogatories of William Flint, et al., 06 Nov. 1829; James Condon's Answers to Interrogatories, 26 October 1829. McDaniel, 67-72. Charlotte, Bill of Sale, James Condon to Henry Clay, 12 May 1806. [back]

16. For more on Dupee's sale to Clay, Henry Clay biographers David and Jeanne Heidler include Aaron as also being instrumental in pushing for Charlotte's purchase, see Heidler, 217. Condon, in an 1829 letter to Clay, argued that Charlotte was sold "by her own pressing solicitation," placing the blame squarely on Charlotte for wanting to live with her new husband. James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, HCP, 7:631-632.; Lidsey Apple. The Family Legacy of Henry Clay: In the Shadow of a Kentucky Patriarch. Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 2011, pp. 80. Letter to Henry Clay from Anne Brown Clay Erwin, 07 January 1832, HCP, 8:440-441; H. Clay and Richard L. Troutman. "The Emancipation of Slaves by Henry Clay." The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 2 (1955): 181; Heidler, 85; Robert Pierce Forbes. The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery & the Meaning of America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007, pp. 14, 24, 44, 117. For more on the environment of slavery in Kentucky, see Anne Twitty. Before Dred Scott: Slavery and Legal Culture in the American Confluence, 1787-1857. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 3, 43-44. Harold D. Tallant. Evil Necessity: Slavery and Political Culture in Antebellum Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2003, 1-3. [back]

17. Forbes, The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath, pp. 5-8, 210-217. [back]

18. George E. Hutchinson, The History of Madison Place, Lafayette Square, Washington, D.C. (Washington, D.C.: The Federal Circuit Bar Journal, 1998), 1-2, 4-7, 14; Southern City, National Ambition: The Growth of Early Washington, D.C., 1800-1860, Octagon Research Series (George Washington University Center for Washington Area Studies, 1995), iv; "James K. Paulding (1838–1841)," Miller Center, October 4, 2016; "Decatur House: Design and Designer," by Paul F. Norton, in Decatur House, Helen Duprey Bullock and Terry B. Morton, eds. (Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1967), 9-12; Patrick Hoehne, Kaci Nash, and William G. Thomas III. "Mapping Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family: 1822." O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C. Law & Family, 2018, Using Esri Story Maps (accessed April 15, 2019); Dendrochronology Report of the Oxford Tree Ring Laboratory, Report 2012/05, "The Tree-Ring Dating of the Slave Quarters at Decatur House, Jackson Place, Washington, D.C.," by Michael J. Worthington and Jane I. Seiter. [back]

19. Mary Beth Corrigan, "The Ties That Bind: The Pursuit of Community and Freedom Among Slaves and Free Blacks in the District of Columbia, 1800-1860," in Southern City, National Ambition: The Growth of Early Washington, D.C., 1800-1860. Octagon Research Series. (Washington, D.C.: George Washington University Center for Washington Area Studies, 1995), 71-73; Receipts for payments to an agent of St. John's Church, The Family Papers of Henry Clay, Manuscript Division, MSS16105, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Part II, Box 51, "Business Records: July 1825-May 1827."; Letitia W. Brown, "Residence Patterns of Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1800-1860," Historical Society of Washington, D.C. 69/70 (1969, 1970): 69; Thomas et al.,"Mapping Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family: 1822." O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C. Law & Family, 2018 (accessed April 15, 2019). [back]

20. Harold D. Tallant. Evil Necessity: Slavery and Political Culture in Antebellum Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2003. [back]

21. "Memorial of Inhabitants of the District Of Columbia, Praying for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the District," 23rd United States Congress, 2st Session, House of Representatives, 24 March 1828, Doc. No. 140, printed with names attached on 09 Feb. 1835, 1-10, signatures on pp. 3-10. In O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, edited by William G. Thomas III, et al. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed October 11, 2015. For an additional look into slavery in the District in the year before Dupee's suit, see "Slavery in the District of Columbia," Register of Debates, U.S. House of Representatives, 20th Congress, 2nd Session, 06 January 1829. For an additional look into slavery in the District in the year before Dupee's suit, see "Slavery in the District of Columbia," Register of Debates, U.S. House of Representatives, 20th Congress, 2nd Session, 06 January 1829. [back]

22. Charlotte, Petition for Freedom, to the Judges of the Circuit Court of D.C. from Robert Beale, 18 Feb. 1829; Defendant's (Clay/Dawson) Interrogatories to James Conden [sic], 13 Aug. 1829; James Condon's Answers to Interrogatories, 26 Oct. 1829; Answers to Interrogatories of Ezekiel Richardson et al., 06 Nov. 1829; Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, HCP, 7:630-632. [back]

23. The Family Papers of Henry Clay, Vol XIV, 24 Nov. 1828 - 14 March 1829, Microfilm: Reel 3: Letter from Nathaniel Williams to Henry Clay, 24 Feb. 1829, Letter and invitation for Clay to party at Mansion Hotel, 06 March 1829, 16 March-11 Nov. 1829, Microfilm: Reel 3.; William G. Thomas III, A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation's Founding to the Civil War, MANUSCRIPT. New Haven: Yale University Press, November 2020, pp. 7-8, 16, 21, 50, 76. W. Caleb McDaniel gives attention to freedom suits and other strategies to freedom in Kentucky, as well as the state's slave laws around the time Charlotte lived in the state. See McDaniel, Sweet Taste of Liberty, pp. 19-90. [back]

24. HCP, Letter from Henry Clay to the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, 18 Feb. 1829, 7:622-24. [back]

25. List of Mayors of Nashville, Tennessee: 1806-Present, Nashville Archives; Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, HCP, 7:630-632. [back]

26. Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, HCP, 7:630-632. [back]

27. Ibid.; James Condon's Answers to Interrogatories, October 26, 1829. Charlotte v. Henry Clay. In O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, edited by William G. Thomas III, et al. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed October 09, 2020. [back]

28. Ibid.; Answers to Interrogatories of Ezekiel Richardson et al., 06 Nov. 1829. [back]

29. HCP, Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, 7: 631-32; James C. Klotter, Henry Clay: The Man Who Would Be President. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 194; Heidler, 217-218. [back]

30. HCP, Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, 7: 631-32; William G. Thomas III. "The Timing of Queen v. Hepburn: An exploration of African American Networks in the Early Republic." In O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, edited by William G. Thomas III, et al. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed October 09, 2020. [back]

31. HCP, Letter from Henry Clay to George W. Dawson, 08 July 1829, 8: 72-73.; Letter from Nathaniel Williams to Henry Clay, 24 Feb. 1829, Family Papers of Henry Clay, vol. 14, November 24, 1828 - March 14, 1829. [back]

32. Letter from Philip Fendall to Henry Clay, 17 Aug. 1830 and 10 Sept. 1830, HCP, 8:252-253, 260-263. [back]

33. The Family Papers of Henry Clay, Vol. XV, 16 March - 11 Nov. 1829, Letter from Philip Fendall to Henry Clay, 24 March 1829. In this letter, Fendall pledges to "being honored with any commands from you which I may be capable of executing, nor my anxiety to testify the attachment to you which on every personal and public ground I must always and profoundly feel."; Letter from Philip Fendall to Henry Clay, 17 Aug. 1830 and 10 Sept. 1830, HCP, 8:252-253, 260-263. [back]

34. James C. Klotter. Henry Clay: The Man Who Would Be President. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 194. [back]

35. HCP, Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, 7: 631-32; Letter from Philip Fendall to Henry Clay, 17 Aug. 1830 and 10 Sept. 1830, HCP, 8:252-253, 260-263. [back]

36. Letter from Philip Fendall to Henry Clay, 17 Aug. 1830 and 10 Sept. 1830, HCP, 8:252-253, 260-263. [back]

37. Deborah Gray White, Ar'n't I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1985), 47-49. Letter from Anne Brown Clay Erwin to Henry Clay, The Papers of Henry Clay, 07 January 1832, HCP, 8:440-441. [back]

38. Lindsey Apple, The Family Legacy of Henry Clay: In the Shadow of a Kentucky Patriarch (Lexington: The University of Kentucky Press, 2011), 80.; HCP, Letter from James Condon to Henry Clay, 01 March 1829, 7: 631-32; Henry Clay and Richard L. Troutman, "The Emancipation of Slaves by Henry Clay," The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 2 (1955): 179-181; Heidler, 217-218. [back]