A Mother's Inheritance: Women, Interracial Identity, and Emancipation in Maryland, 1664-1820

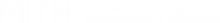

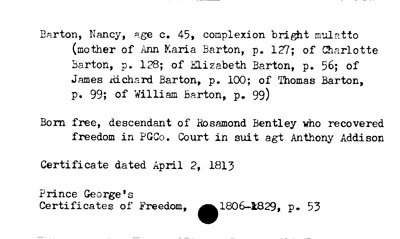

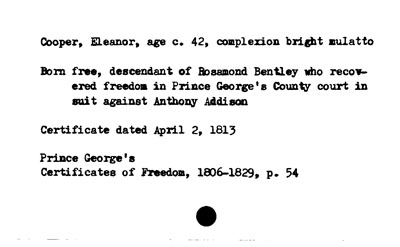

On November 3, 1813, Elizabeth Barton, a "bright mulatto," appeared at the Prince George's County courthouse in Upper Marlboro, Maryland in order to obtain a certificate of freedom in keeping with an 1806 law. The court clerk, John Read Magruder, Jr., recorded that the twenty-year-old Barton was "born free, reputed dau[ghter] of Nancy Barton who recovered her freedom in Prince George's County Court in a freedom suit against Anthony Addison."1 In addition to Elizabeth, other members of her family made visits to the court that were recorded: Elizabeth's mother, Nancy, and her aunt, Eleanor, in April 1813; as well as Elizabeth's siblings: James and William in 1818, Charlotte and Ann in 1819, and Thomas in 1824.2

However, to tell this family's story, I must begin in late seventeenth-century Maryland, when a white indentured servant named Mary Davis married an enslaved black man named Domingo. Their union set the stage for a multi-generational legal struggle across multiple jurisdictions that was shaped by over 150 years of Maryland and national laws, from the late seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries.

This story begins in late seventeenth-century Maryland, when a white indentured servant named Mary Davis married an enslaved black man named Domingo, a union which set the stage for a multi-generational legal struggle across multiple jurisdictions and shaped by over 150 years of Maryland and national laws.

Freedom suits not only tell us how race and slavery worked on a local level, they also help us reconstruct the family histories of enslaved people. Family stories allow us to see change over time in the legal system, as well as in the evolution of racial definitions in early America. Many scholars have discussed the fluid nature of race in early American history.3 Notions of difference were often tied to religion. English people, along with Western Europeans more generally, saw the world as divided between Christians and "heathens," at times even coming close to equating "race" with "religion."4 As the century came to a close, legislators strengthened the institution of slavery and in the process, began to move to a notion of race that would increasingly be based on biology. They began to legally tie race, sex, and labor together in their efforts to regulate sexual relationships between enslaved men and white women.5 As we will see, this had important implications for enslaved people's efforts to obtain their freedom through the courts.

The Davis Generations

Mary Davis, was born in London, England, in the mid-seventeenth century. The exact date is not known, nor is much known about her life in London prior to her arrival in Maryland in the late seventeenth-century. It is believed that her father's name was Richard Davis and she had a brother, John, who lived on Mark Lane in the shadow of the Tower of London. The circumstances of Mary Davis' indenture are uncertain, although a 1779 court deposition asserts that she was brought to Maryland before 1677 as an indentured servant by Charles Calvert, the Third Lord Baltimore and Proprietor of the Province of Maryland. Sometime after her arrival, Davis met and married a black man by the name of Domingo who was enslaved by Joseph Tilley in Calvert County, MD.6

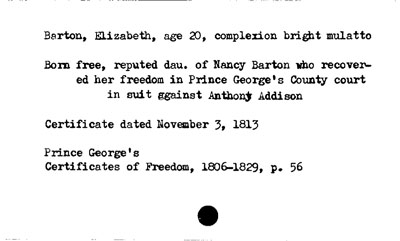

Though interracial marriages did not become illegal in Maryland until 1717, laws passed in the late seventeenth century served as deterrent for such marriages, especially those between white women and black men.7 An 1664 act stated that all black or enslaved people who were currently residing in Maryland, as well as any enslaved people to be imported in the future, were to be enslaved for life—also known as the durante vita clause.8 The law also sought to limit interracial relationships, further legislating that any "freeborne English women forgettfull of their free Condicon" who married an enslaved man condemned herself to servitude for the duration of her husband's life. Any children born to these relationships after 1664 were to be "Sla[v]es as their ffathers were for the terme of their lives," while any children already born to such relationships prior to the passage of the law were to serve until the age of thirty-one.9

The 1664 law deeply affected the lives of Mary and Domingo's children. On March 14, 1677, their son, Thomas, was born in Calvert County, MD; seven years later, on August 11, 1684, a daughter, Rose, was born in St. Mary's County, MD. Both children were born on properties owned by Lord Baltimore, who by 1684, had moved back to England to settle a land dispute with William Penn over the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania.10 In 1692, Colonel Henry Darnall, acting as attorney for Lord Baltimore, successfully petitioned the government for legal possession of these properties, most likely allowing Darnall to obtain possession of the enslaved laborers, including the Davis family.

Nearly twenty-five years later and after subsequent relocations to a Darnall home in Anne Arundel County, a thirty-one-year-old Rose Davis petitioned Henry Darnall II for her freedom in August 1715 in Annapolis. The timing of her petition, after her 31st birthday, was significant. By waiting until she reached the age of thirty-one, Rose clearly believed that she reached the end of her term of service, in accordance with one clause of the 1664 law that provided for some children born to white women and black men to serve until they were thirty-one years old. However, this only applied to those children born prior to the passage of the law. Rose was not.11

Rose's birth after the passage of the 1664 law made her susceptible to the durante vita clause that rendered children born after its inception slaves for life—a fact that Rose was perhaps not aware of. Most of the 1664 law was repealed in 1681, including the portion that punished English women for intermarriage.12 This change unfortunately did not apply to women who were in such relationships prior to 1681, such as Mary Davis. Additionally, the lawmakers in 1681 strengthened the durante vita clause, which guaranteed that all enslaved people already living in Maryland and any children born to them were to be enslaved for life, regardless of any white parentage.13

However, additional components of Rose's freedom petition provide a look into the flexibility of the law during the late seventeenth century. While the durante vita clause proved detrimental to Rose's legal argument, she presented, as evidence of her parentage, an inscription in a Bible in which her mother, Mary Davis, allegedly wrote a short but thorough family history. This genealogy included Rose's birth date, where she was baptized, and the names of her godparents. Most importantly, Mary referred to both of her mixed-race children as being of the "Christian Race."14

The significance of Mary Davis' family record can be found in the ideology of the time. Because societal differences were based, in part, on religion in the seventeenth century, theology shaped the way that Europeans viewed what we now call "race." Historian Rebecca Anne Goetz argues that the importance of baptism in Christianity helped to create a sense of superiority amongst the English which allowed them to categorize society into simple divisions: Christian and heathen, which they often equated with white and non-white.15 To be Christian was to be endowed with the rights guaranteed to all Englishmen (and other Western Europeans). The importance of baptism was not lost on the enslaved or their enslavers, who often treated missionaries with disdain as they feared that baptism allowed their slaves to improve their social status from "other" to that of "Christian."16

By writing an inscription in her family Bible and entrusting it to her children, Mary Davis, a white woman, hoped to control the identity that society assigned to her mixed-race children. Unfortunately, in 1671, the Maryland General Assembly passed a law that stated, in part, that any enslaved persons who were or would be baptized as Christian before or after their importation into the province at the time of the passage of the law would not be granted manumission. Essentially, slavery was presumed to be a natural state for Africans, regardless of baptism.17

The Maryland General Assembly passed a law in 1671 that stated, in part, that any enslaved persons who were or would be baptized as Christian before or after their importation into the province would not be granted manumission. Essentially, slavery was presumed to be a natural state for Africans.

The final nail in the coffin for Rose's case came just a few months prior to her petition when, in 1715, the Maryland General Assembly passed an act that stated, in part, that all enslaved blacks living in Maryland and their children "shall be Slaves dureing their naturall lives." This made the English doctrine of partus sequitur partem—a doctrine that might have been useful to Rose—null and void. It also reinforced the 1671 act by stating that "no Negroe or Negroes by receiving the holy Sacrament of Baptism is hereby Manumitted or sett free nor hath any right or title to freedom."18 With these legal impediments, on March 13, 1716, the Anne Arundel County justices decided that "Rose the Mulato and petr. Afsd serve during Life as a Slave."19

Sometime after 1716, Rose was relocated to a Darnall property in Prince George's County, where according to a 1784 deposition by Henry Darnall III, she attempted to apply for her freedom at least two or three additional times. It was here in Prince George's County, that the lives of the Davis family become even more intertwined with influential Marylanders. From 1728 to 1751, Rose was likely shuttled back and forth between Anne Arundel and Prince George's counties. In 1728, Henry Darnall II and his wife, Ann, sold nearly 3,000 acres of land to Captain John Hyde of London as a result of debt. In addition to the land, eighty-two enslaved people were sold.20 After the initial sale, the property (land and enslaved) underwent a series of ownership transfers. Upon Captain John Hyde's death in 1732, his son, Samuel Hyde inherited the property. Falling into debt, a public sale of Hyde's Prince George's County property was held on June 27, 1750. At this public sale, an almost sixty-six-year-old Rose, and possibly some of her children, were purchased by Benedict Swingate Calvert, the natural son of Charles Calvert, the Fifth Lord Baltimore.21

Swingate Calvert resided on estate called Mount Airy in Prince George's County, located just a few miles from where many of Rose's children were enslaved in the county seat of Upper Marlboro.22 According to a 1781 deposition, Swingate Calvert allowed Rose to go about as she pleased because she was past plantation service.23 Rose spent the rest of her life enslaved at Mount Airy.

The Bentley Generations

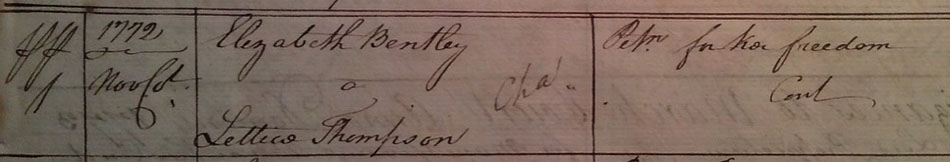

After Rose's freedom petition, Mary's descendants did not make another legal attempt for freedom for another fifty-seven years. The details surrounding this subsequent case came from a 1779 deposition in the freedom suit of Rosamund Bentley, the known granddaughter of Rose Davis. According to Catherine Harley, a woman by the name of "Indian Polly"—who was Rosamund's mother—applied for freedom from Lettice Thomson of Upper Marlboro in 1772, but the case did not continue due to Indian Polly's death from smallpox.24 The only other evidence to corroborate Harley's claim came by way of an entry in the Prince George's County Court docket for 1773 which showed that an Elizabeth Bentley petitioned Lettice Thomson for her freedom in 1772.25

Perhaps this Elizabeth Bentley and Indian Polly were the same person? Although smallpox took her life, like her mother before her, Elizabeth "Indian Polly" Bentley passed the desire for freedom on to her children: Rosamund, Mary, Nell, Margaret, and William.26

Of Indian Polly's five children, Rosamund was the first to petition for freedom. Rosamund petitioned Anthony Addison for her freedom in 1779.27 Thomas Stone of Charles County, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, represented Addison. Rosamund was represented by Captain John Allen Thomas, a war veteran and slave owner from St. Mary's County.28 It is not known whether Thomas worked for a fee or pro bono. There are other examples of lawyers who were slave owners representing enslaved people in their freedom suits pro bono, including Thomas Jefferson and Francis Scott Key.29 Often their reasoning for taking on such cases was because they believed that their particular client deserved justice.30

In her petition, Rosamund demonstrated an awareness of her family's history when she stated that she was petitioning not only on behalf of herself, but also on behalf of her siblings and "some others of her ancestor[s]."31 Rosamund hoped to leverage her knowledge in order to challenge her enslavement, explaining to the court that her "Great Grandmother (re: Mary Davis) was an English Woman Born and came into this Province with Lord Baltimore. The said Mary Davis had the fortune of having an Indian Native of this Country for her husband and by him had your petitioner's grandmother."32

In the Davis family Bible, Mary explicitly referred to her husband as a "Negro." Although the lines between racial categorizations were not yet well-defined in seventeenth-century Maryland, people generally made distinctions between American Indians and Africans. It is highly probable that Domingo was indeed African, due to Mary Davis' characterization. So why did Rosamund change his ethnic identity?

By implying that Domingo was actually American Indian, and, by inference, free, Rosamund argued that a misnomer led to the unjust detainment of her family for three generations. C. S. Everett argues that because of the ever-changing concept of race, there were a variety of labels that could be applied to a person: "Slave owners . . . recognized 'white' Indians, 'mulatto' Indians, and 'Negro' Indians as well as just plain Indians."33 But did Rosamund have proof? She had to rely on the testimony of two white individuals, William Dove and Catherine Harley, both of whom stated that Rosamund's grandmother, Rose, was the daughter of Mary Davis and that she was "begotten by an East India Indian who came into this Country with Lord Baltimore."34 There is some debate amongst scholars as to whether there is a distinction between the labels of "East Indian" versus "Indian."35 Regardless, it is safe to assume that Rosamund assigned non-African origins for her great-grandfather as a way to bolster her case. By claiming non-African ancestry, Rosamund essentially argued that the status of her ancestors—namely Rose Davis—was not subject to the 1664 law that condemned her to enslavement. Rosamund's decision is a reflection of late eighteenth-century sentiments towards American Indians. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson regarded the enslavement of American Indians as an "inhuman practice."36 Such views were in stark contrast to those of the early settlers of the seventeenth century who viewed indigenous people as "primitive" and "uncivilized."37 This shift in the social and legal landscape would have been noticed by freedom petitioners.38

Rosamund's decision to assign non-African origins to her great-grandfather as a way to bolster her case reflects a shift in late eighteenth-century sentiments towards American Indians. Thomas Jefferson's view of the enslavement of American Indians as an "inhuman practice" were in stark contrast to those of seventeenth-century settlers who saw indigenous people as "primitive" and "uncivilized." This shift in the social and legal landscape would have been noticed by freedom petitioners.

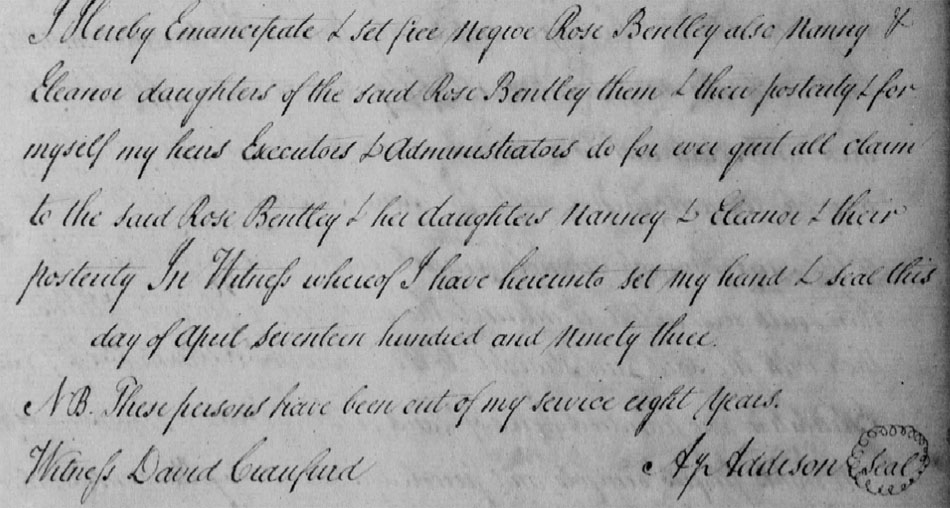

It is not possible to know whether or not Rosamund intentionally misled the court. Regardless of her intentions, her petition was successful, as Addison was unable to provide contradictory testimony. After some delays, the case finally concluded in August 1781, when the court determined that Rosamund Bentley should "be absolutely free and Discharged from the Services of the said Anthony Addison."39 Despite that determination, Rosamund and her daughters, Nancy and Eleanor, did not receive their manumission papers for at least four more years.40

While no records related to Rosamund exist after 1793, she likely remained nearby like her daughters and her descendants who were still living in the area throughout the early nineteenth century, although definitive proof has not been obtained.41 Unlike Virginia, Maryland did not force freed blacks to leave the state.42 If she did remain, Rosamund was most likely employed as a free laborer on a local farm or plantation. In doing so, Rosamund might have been able to maintain contact with her siblings who were still enslaved.

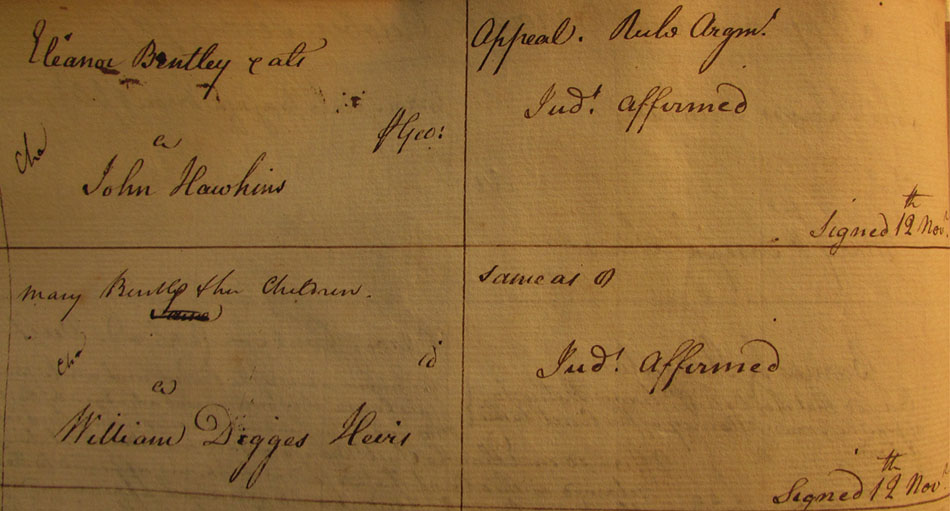

In November 1781, Rosamund's sisters, Eleanor and Mary Bentley, filed their own petition.43 Upon the death of Lettice Thomson in 1776, Nell became the property of Captain John Hawkins.44 Mary Bentley was enslaved by William Digges nearly fifteen miles away.45 Nell and Mary modeled their case after Rosamund's. In front of the same justices, Nell and Mary mentioned her case as a reminder of the judges' previous decision. The two women even provided the depositions by Dove and Harley and chose John Allen Thomas to represent them. Thomas Stone, once again, represented Hawkins and Digges. This had all the makings of a judicial rematch, but events did not transpire the same way.

Perhaps learning from the previous case, Stone obtained eight depositions from various individuals connected to the Davis family, including Henry Darnall III, and William Digges, a cousin of the defendant. Thomas obtained additional petitions, including one from Archbishop John Carroll. All the aforementioned deponents were cousins, providing further evidence of how intertwined the lives of the enslaved and the slave owners were. The death of defendant William Digges in 1782 and the time needed to gather the depositions delayed the case for three years.

The defense depositions proved to be quite effective, as they called into question the statements made by Dove and Harley. Laura F. Edwards argues that the judicial system of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries often relied on memory in court testimony. The perceived character of the witnesses, "credible white men's information—opinions, really—literally created truth. What they said could validate or invalidate a charge, elevating their versions of events over others."46 The character of certain witnesses could be put on trial, which is evident regarding the comments about Catherine Harley as "a woman of very infamous Character dealing with Negroes and being kept by a Negro man as his wife or mistress. That she was reputed to be a common strumpet."47

Laura F. Edwards argues that the judicial system of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries often relied on memory in court testimony. The perceived character of the witnesses, "credible white men's information—opinions, really—literally created truth. What they said could validate or invalidate a charge, elevating their versions of events over others."

Despite the acknowledgment of Rosamund's success and the use of her same petition, the various defense depositions severely hurt Nell and Mary's case, which the justices determined "groundless" and marked the sisters and their children as slaves. A 1785 appeal to the General Court of the Western Shore in Annapolis proved unsuccessful.48

What happened to Mary Bentley after the appeal is unknown. Nell Bentley was shortly thereafter removed to Virginia.49 Five years later, her daughter, Elizabeth, and her grandchildren, were sold to William Keen, and subsequently Thomas Keen of Washington, D.C. Nineteen years later, in 1809, Elizabeth petitioned Keen for her freedom, continuing the litigious tradition of her family.50

Elizabeth based her argument for freedom on her descent from Mary Davis, similar to the argument made by Rose Davis. She also argued that her removal to Virginia was unlawful, and that she and her children were unlawfully held as they were born after she was entitled to her freedom. It is not clear what she based the latter argument on, but the trial ended after just five days with Elizabeth and her family obtaining their freedom.51 What happened to Elizabeth and her children after their success is unknown. Perhaps they moved back to Prince George's County to be near family and where their skills as laborers were more useful.

The significant increase in the free black population after the Revolutionary War caused alarm amongst white legislators. Capitalizing on the increased contempt towards blacks, wealthy white men began to persuade white men with lower means that they had a common interest in preserving the liberty for which they had fought. The system of slavery needed to be preserved, and the increasing presence of free blacks threatened that system.

The free black population in Prince George's County increased following the American Revolution. According to the 1790 Federal Census, there were only 164 free blacks residing in the county. By 1820, that number jumped to 1,096.52 This significant increase in the free black population caused alarm amongst white legislators. Capitalizing on the increased contempt towards blacks, wealthy white men began to persuade white men with lower means and status that they had a common interest in preserving the liberty for which they had fought. The system of slavery needed to be preserved, and the increasing presence of free blacks threatened that system.53 The assumption prevailed that free blacks were depraved, drunken vagrants and criminals, and lawmakers used these beliefs as proof that emancipation was dangerous to society.54 As a result, greater restrictions were put on the liberty of free blacks. For example, a 1796 law denied the right to vote to those who were manumitted after its passage. It also prohibited free blacks from testifying in court against whites. These two clauses reinforced the idea that blacks—free or not—had no rights as citizens.55 More of these laws appeared throughout the course of the early nineteenth century, greatly impacting the lives of free blacks like Rosamund's descendants.

The Barton Generations

Rosamund's daughters, Nancy Barton and Eleanor Cooper, made an appearance in 1813 in the Prince George's County Register of Free Blacks.56 Despite the previous record of their freedom, the two sisters were abiding by an 1806 Maryland law that required, in part, that all freedom certificates were to be granted by the county clerk. This directed individuals who were previously manumitted, like Nancy and Eleanor, to obtain new certificates in accordance with the law. To do so, they were required to provide testimony to the clerk as to how they obtained their freedom.57

The main reason for the 1806 law regulating certificates of freedom for free blacks was white fear. Regulation was prompted by what the legislature described as "great mischiefs [that] have arisen from slaves coming into possession of the certificates of free negroes, by running away and passing as free, under the faith of such certificates." The law mandated that certificates of freedom were only valid if they were granted by clerks of the county courts. The certificates were required to document height, age, complexion, the time the black person became free, where they were raised, and any noticeable marks. Any blacks who were manumitted prior to the passage of the law had to prove their freedom to the registrar via testimony.58

On the surface, the passage of this act appears to have been for the benefit of free blacks so that they would not fall victim to the theft of their freedom papers. However, this law is indicative of the changing legal climate for free blacks in early national Maryland. Jennifer Hull Dorsey claims that this new system for freedom certificates provided whites with a way to distinguish free black laborers from enslaved laborers who earned wages.59 But according to Dorsey, it is incorrect to assume that free blacks obtained these certificates out of a desire to abide by the law or they believed it protected their freedom.60 They did so because freedom certificates afforded them the ability to travel as they pleased in search of new opportunities.61

The promise of new opportunity did not come without its obstacles. A series of laws appeared in the early nineteenth century that made it increasingly difficult for free blacks to become independent in rural slave societies. One such law, passed on the same day as the 1806 law concerning manumission, stipulated that free blacks needed to have a license to sell corn, wheat, and tobacco.62 Dorsey stresses that these licensing requirements worked to deter free blacks from becoming small farmers, which reaffirmed their dependence on the planter class.63

A law that impacted free black women was passed in 1809. It stipulated that the status of any child born to an enslaved woman before her term of service ended—generally as the result of a decree of will or manumission—was to be that of a slave.64 What makes this law significant is that it specifically targeted enslaved women, tying their bodies to the legal system.65 Jessica Millward suggests that manumissions held particular consequences for black women and men, as it was maternal descent that determined a slave's status. As a result, black women were essential to freedom petitions, as they manipulated the legal system to their own advantage and shaped "their own legal destinies—and those of their progeny."66

Black women were essential to freedom petitions, as they manipulated the legal system to their own advantage and shaped "their own legal destinies—and those of their progeny."

Conclusion

In discussions of the experiences of enslaved people in America, historians are often confronted with the concept of "agency." Walter Johnson argues that the general focus amongst new social historians regarding the "agency" of enslaved people tends to overlook how they "set about forming social solidarities and political movements at the scale of everyday life. How did they talk to one another about slavery, resistance, and revolution?"67

With Mary and Rose Davis, we can observe the law intertwining slavery and race from the late seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries, as slavery became the dominate labor system. In the cases of Indian Polly and Rosamund Bentley, we see how the American Revolution created favorable circumstances for enslaved people. Yet the case of Nell and Mary Bentley shows just how small that window of opportunity was. Even more important were the personal stories that are revealed through witness testimony and the language of the petition itself. During a time in which race and slavery were increasingly aligned to the socio-economic structure, the women of the Davis family strategically wielded their family history in the court systems of Maryland, employed the law for their own needs, and exercised a form of power of their own.

Endnotes

1. Louise J. Hienton, Searching for Ancestors Who Were Slaves: An Index to the Freedom Records of Prince George's County Maryland, 1808—1869, "Elizabeth Barton," Archives of Maryland Online, 169 (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

2. Hienton, Searching for Ancestors Who Were Slaves, "Barton, Nancy," April 2, 1813; "Cooper, Eleanor," April 2, 1813; "Barton, Ann Maria," November 3, 1819; "Barton, Charlotte," November 3, 1819; "Barton, James Richard," September 1, 1818; "Barton, Thomas," September 28, 1824; "Barton, William," September 1, 1818, (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

3. An earlier contribution to the discussion of the construct of race came from Winthrop D. Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Towards the Negro, 1550-1812 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1968); Also Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996). [back]

4. Colin Kidd, Anthony S. Parent, and Roxann Wheeler are three historians who have contributed to this discussion. See Colin Kidd, The Forging of Race: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600-2000 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Anthony S. Parent, Foul Means: The Formation of a Slave Society in Virginia, 1660-1740 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Roxann Wheeler, The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000). [back]

5. Brown, Good Wives, 188, 197. Peter Wallenstein explored the legal trend of putting race in the simple categories of white and non-white. Generally, it was assumed that non-white meant black. But in the late-eighteenth century, Wallenstein states that one-third of freedom petitions filed in Virginia between 1792 and 1811 involved enslaved men and women who sued on the basis that they had Native American ancestry and the court sided with each one. However, Wallenstein does not question the validity of these claims. Peter Wallenstein, "Indian Foremothers: Race, Sex, Slavery and Freedom in Early Virginia," in The Devil's Lane: Sex and Race in the Early South, ed. Catherine Clinton and Michele Gillespie, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 62-64. When discussing interracial sex, most historians tend to focus on consensual relationships between white and black people. Only a few have focused on the nonconsensual relationships. See Thelma Jennings, "'Us Colored Women Had to Go Through a Plenty': Sexual Exploitation of African-American Slave Women," Journal of Women's History 1, no. 3 (1990): 45-74; Wendy A. Warren, "'The Cause of Her Grief': The Rape of a Slave in Early New England," The Journal of American History 93, no. 4 (March 2007): 1031-1049; Thomas A. Foster, "The Sexual Abuse of Black Men under American Slavery," Journal of the History of Sexuality 20, no. 2 (Sept. 2011), 445-465. [back]

6. Deposition of William Dove, Rosamund Bentley against Anthony Addison, March 1779, Prince George's County Court (Court Record) 08/1777-03/1782, Book EE 2, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland, henceforth Bentley against Addison, March 1779; Inscription of family Bible by Mary Davis, Rose Davis against Henry Darnall, August 1715, Anne Arundel County Court (Judgment Record) 08/1712—03/1715, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland, henceforth Davis against Darnall, August 1715. [back]

7. "A Supplementary Act to the Act relating to Servants and Slaves," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1717-April 1720, Volume 33, 111-113, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

8. "An Act Concerning Negroes and other Sla[v]es," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, January 1637/8-September 1664, Volume 1, 533-534, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

9. "An Act Concerning Negroes and other Sla[v]es," 533. [back]

10. Robert J. Brugger, Maryland: A Middle Temperament (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 38. [back]

11. Davis against Darnall, August 1715. [back]

12. "An Act concerning Negroes & Slaves," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, October 1678-November 1683, Volume 7, 203-205, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed March 9, 2014). Based on the language of this law, it appears the 1664 law was not repealed for the benefit of the women it affected. Rather, the law was repealed in order to prevent enslavers from forcing people into such marriages as a means to obtain more labor—from the woman and her subsequent children. Financial penalties were imposed on those enslavers and ministers who took part in such coercion; the woman and her children were to be freed. It is important to note that this did not apply to marriages that were consensual; See Hodes, Illicit Sex, 29. [back]

13. "An Act concerning Negroes & Slaves," 203. [back]

14. Davis against Darnall, August 1715. [back]

15. Rebecca Anne Goetz, "From Potential Christians to Hereditary Heathens: Religion and Race in the Early Chesapeake, 1590-1740" (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2006), 152, in ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text (accessed December 3, 2013). [back]

16. Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 60. [back]

17. "An Act for the Encouraging the Importation of Negroes and Slaves into this Province," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly of Maryland, April 1666-June 1676, Volume 2, 272, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed September 20, 2013). [back]

18. "An Act Relating to Servants and Slaves," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly of Maryland, April 26, 1715-August 10, 1716, Volume 30, 289, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed September 20, 2013). [back]

19. Davis against Darnall, August 1715. [back]

20. Prince George's County Court (Land Records), Book M, 315-322, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland. [back]

21. Maryland Gazette June 27, 1750, Maryland Gazette Collection, 1728-1839, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed February 14, 2014); Benedict Swingate Calvert to Charles Calvert, 5th Lord Baltimore, Annapolis, Maryland, November 18, 1746, and Charles Calvert to Swingate Calvert, London, March 4, 1748/9, in R. Winder Johnson, The Ancestry of Rosalie Morris Johnson (Philadelphia: Ferris & Leach, 1905), 25. [back]

22. Anne Elizabeth Yentsch, A Chesapeake Family and their Slaves: A Study in Historical Archaeology (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 263; The identity of all of Rose's children is unknown but some clues have appeared. In a 1781 deposition, Archbishop John Carroll testified that he knew an adult daughter of Rose's who lived with his mother, Eleanor Darnall Carroll, at her home in Forest Glen in Montgomery County, MD after the death of her husband in 1751. Mrs. Carroll would also enslave three more of Rose's descendants, Bentley against Hawkins/Bentley against Digges, November 1781. In 1809, seven Davis descendants petitioned for their freedom in Washington, D.C.: Susan, Letitia, Ann, George, John, Teresa, and Mary Ann. Only Susan was successful, as her case was decided before the 1810 Supreme Court decision of Queen v. Hepburn, which disallowed hearsay evidence. [back]

23. Deposition of Benjamin Becroft Senior, March 19, 1784, Bentley against Hawkins/Bentley against Digges, November 1781. [back]

24. Deposition of Catherine Harley, Bentley against Addison, March 1779. [back]

25. Prince George's County Court, Docket 1772, 5, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland. [back]

26. Not much is known about William outside of his name and I have not located evidence exists to suggest that he petitioned for his freedom. Margaret Bentley was enslaved at the home of Lettice Thomson, according to the estate inventory of James Wardrop. However, Margaret does not appear on subsequent inventories, so her whereabouts after 1760 are unknown. See "Inventory of James Wardrop." [back]

27. Bentley against Addison, March 1779. [back]

28. Thomas served during the Revolutionary War, most notably at the Battle of Long Island as a part of the Maryland 400 in 1776. Thomas was a slave owner. Linda Davis Reno, genealogist of the St. Mary's County Historical Society, email message to author, January 14-16, 2014. [back]

29. In 1770, Thomas Jefferson served pro bono for Samuel Howell, a mixed-race man, who petitioned to be freed from indentured servitude. According to Annette Gordon-Reed, Jefferson worked diligently on the case, which he eventually lost. Jefferson gave Howell money as consolation; Howell, in turn, ran away, possibly with the aid of the funds given to him by Jefferson. See Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 101. [back]

30. Loren Schweninger, "Freedom Suits, African American Women, and the Genealogy of Slavery," The William and Mary Quarterly 71, no. 1, (Jan. 2014): 385. [back]

31. Bentley against Addison, March 1779. [back]

32. Bentley against Addison, March 1779. [back]

33. C. S. Everett, "'They shalbe slaves for their lives': Indian Slavery in Colonial Virginia," in Indian Slavery in Colonial America, ed. Allan Gallay, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 69-70. [back]

34. Bentley against Addison, March 1779. [back]

35. There is some historical evidence to suggest that indentured servants from India arrived in America during the seventeenth-century. In a 2003 study prepared for the Colonial National Historical Park, project historian Martha W. McCartney evaluated the number of African workers living in colonial Jamestown under the headright system.With this system, planters used the importation of Africans as a way to obtain more acres. One such planter, George Menefie, used "Tony, as East Indian" to obtain additional acreage. This places East Indians in America as early as 1642, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619-1803, by Martha W. McCartney (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 2003) 52, (accessed February 26, 2014). Additionally, research conducted by genealogist Paul Heinegg shows that East Indians were present in colonial Maryland as early as 1676. Estate inventories show East Indians servants listed separately from Negro slaves. Heinegg suggested that East Indians came into the country as indentured servants who easily blended into the free African American population once their indentures were complete, although the same could be said about the Native American population. Yet despite Heinegg's extensive archival research, there is no definitive proof that these individuals were from Southeast Asia. See Heinegg, "East Indians of Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina" (accessed March 8, 2014). [back]

36. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (London: John Stockdale, 1787), 100 (accessed February 15, 2014). [back]

37. Jean B. Russo and J. Elliott Russo, Planting an Empire: The Early Chesapeake in British North America (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University, 2012), 27. [back]

38. Brown, Good Wives, 223. [back]

39. Bentley against Addison, March 1779. [back]

40. Historian Jennifer Hull Dorsey suggests that it is possible that masters often delayed the actual date of manumission in order to obtain economic compensation for the trial proceedings. David Skillen Bowen correctly observes that the immediate enforcement of a manumission required someone to act in the interest of the enslaved, which was unlikely to occur. See Jennifer Hull Dorsey, Hirelings: African American Workers and Free Labor in Early Maryland (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011), 64; David Skillen Bowen, "The Maryland Context of Dred Scott: The Decline in the Legal Status of Maryland Free Blacks, 1776-1810," The American Journal of Legal History 34, no. 4 (Oct. 1990): 384, especially note 15. [back]

41. The registration of Rosamund's daughters, Nancy and Eleanor, as free blacks in Prince George's County in 1813 is evidence that they remained in the area after obtaining their manumission certificate in 1793. It is a logical assumption that if her daughters remained, Rosamund did as well. See Hienton, "Barton, Nancy," April 2, 1813; and "Cooper, Eleanor," April 2, 1813 (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

42. Loren Schweninger highlights cases in which enslaved women petitioned the Virginia court for permission to remain in the state. One such woman argued that moving to another state, "in the midst of Strangers, cut off from the society and aid of relations and friends," would be insufferable. See Legislative Petitions, Petition of Nancy to the Virginia General Assembly, Dec. 7, 1813, Cumberland County, LVA), quoted in Loren Schweninger, "The Fragile Nature of Freedom: Free Women of Color in the U.S. South," in Beyond Bondage: Free Women of Color in the Americas, ed. David Barry Gaspar and Darlene Clark Hine (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 110. [back]

43. It appears from the document that Eleanor initially submitted her petition in August 1781, the same month Rosamund obtained her freedom. However, Eleanor and Mary appear as co-petitioners in November of that same year. [back]

44. Will, "Lettice Sims," Prince George's County Register of Wills (Wills), Book T 1, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland. [back]

45. William Digges was the grandson of the Colonel William Digges who resided at Notley Hall, when Rose Davis was baptized there. His father represented Henry Darnall II in Rose Davis' freedom suit. [back]

46. Laura F. Edwards, "Enslaved Women and the Law: Paradoxes of Subordination in the Post-Revolutionary Carolinas," Slavery and Abolition 25, no. 2 (August 2005), 312. [back]

47. Eleanor and her children against John Hawkins/Mary Bentley and her children against William Digges Heirs, November 1781, Prince George's County Court (Court Record) 08/1782-03/1784, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland, henceforth Bentley against Hawkins/Bentley against Digges, November 1781. [back]

48. General Court of the Western Shore, Docket 1787, 168, Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, Maryland. [back]

49. In John Hawkins' 1802 estate inventory, there is an adult enslaved woman listed by the name of Poll, along with her children: Nancy, Patty, and an unnamed infant. Although her age is not provide, it is possible that this Poll is Nell's daughter who was observed on the previously discussed inventories. See "Inventory of John Hawkins," Darnall's Chance House Museum, Upper Marlboro, MD, trans. Barbara Sikora. [back]

50. Elizabeth Bentley v. Thomas Keen, June 1809, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 21, Entry 6, Box 2. [back]

51. Elizabeth Bentley v. Thomas Keen. Minute Book Entry, June 1908, National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 21, Microfilm 1021, Reel 1. [back]

52. Susan Fitch Daniels, "The Effects of the Civil War and Emancipation on the Black Population of Prince George's County, Maryland" (M.A. thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, 1990), attachment 2. Despite this increase, the enslaved population of Prince George's County, the highest in the state, remained at the same level from 1790 until 1810. Although Maryland banned the importation of blacks in 1796 (and freed any illegally imported slaves), the increased population was the result of an increase in natural births, which saw the population double in the Chesapeake region from 1755-1782. See T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997), 9; "An ACT relating to negroes, and to repeal the acts of assembly therein mentioned," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1796, Archives of Maryland Online, Volume 105, 249-256 (accessed March 9, 2014); Dorsey, Hirelings, 17. [back]

53. Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2013), 30. Taylor argues that a motivation for only land-owning white men to have the right to vote was because they did not trust westerners and poor whites (who generally had little to no slaves) to preserve the institution. This motivation manifested itself in the "Three Fifths" clause of the Constitution. See Taylor, Internal Enemy, 34. [back]

54. Taylor, Internal Enemy, 40. In 1825, Maryland passed a law that mandated that African Americans who were found to have "no obvious means of employment" were to be fined $30, "An additional supplement to the act relating to negroes, and to repeal the acts of assembly therein mentioned," General Assembly December 26-1825 - March 9, 1826, Session Laws, Archives of Maryland Online, Volume 402, 128-130 (accessed March 29, 2014). [back]

55. "An ACT relating to negroes, and to repeal the acts of assembly therein mentioned," Proceedings and Acts of the General Assembly, 1796, Archives of Maryland Online, Volume 105, 249-256 (accessed March 9, 2014). [back]

56. Hienton, "Barton, Nancy," April 2, 1813; "Cooper, Eleanor," April 2, 1813 (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

57. "An ACT, entitled, An additional supplement to an act, entitled An act relating to negroes, and to repeal the ads of assembly therein mentioned," General Assembly (Laws) November 4, 1805—January 28, 1806 Session Laws, Volume 607, 46-47, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed September 5, 2013). [back]

58. "An ACT, entitled, An additional supplement to an act, entitled An act relating to negroes, and to repeal the ads of assembly therein mentioned," 46-47. [back]

59. Dorsey, Hirelings, 49. [back]

60. Dorsey states that it is incorrect to assume that freedom certificates protected free blacks from re-enslavement. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass recounted in his autobiography that "cases have been known, where freemen have been called upon to show their papers, by a pack of ruffians—and, on the presentation of the papers, the ruffians have torn them up, and seized their victim, and sold him to a life of endless bondage." Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, 1855 (New York: Dover, 1969), 286 as quoted in Dorsey, Hirelings, 50. [back]

61. Dorsey likened freedom certificates to contemporary green cards. Hirelings, 53 [back]

62. "An ACT to prevent free negroes from selling any corn, wheat or tobacco, without having a license for that purpose from a justice of the peace," Session Laws, Archives of Maryland Online, Volume 607, 60 (accessed March 9, 2014). Dorsey argues that despite free blacks obtaining these licenses, white planters mostly preferred to hire white tradesmen. Hirelings, 36-37. [back]

63. Dorsey, Hirelings, 84. [back]

64. "An ACT to ascertain and declare the condition of such Issue as may hereafter be born of Negro or Mulatto Female Slaves, during their servitude for Years, and for other purposes therein mentioned," General Assembly, November 6, 1809 - January 8, 1810, Session Laws, Volume 570, 117-118, Archives of Maryland Online (accessed March 9, 2014). [back]

65. Jessica Millward, "'A Choice Parcel of Country Born': African Americans and the Transition to Freedom in Maryland, 1770-1840," (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2003), 364. [back]

66. Millward, "That All Her Increase Shall Be Free," 367. [back]

67. Walter Johnson, "On Agency," Journal of Social History 37, no. 1 (Fall 2003): 118. [back]