"I Did Not Want to Go": An Enslaved Woman's Leap into the Capital's Conscience

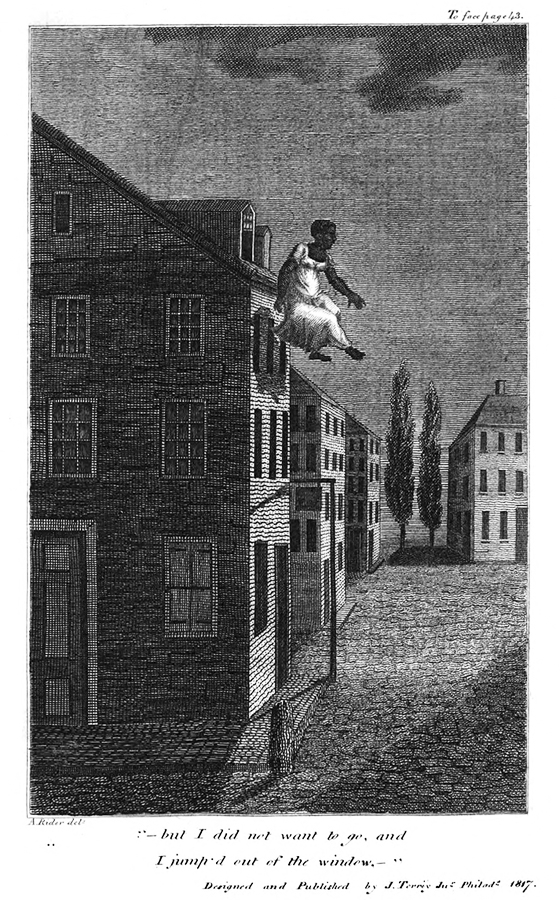

The woman known as Anna awakened at daybreak in November 1815 and jumped from a third floor window of a Washington, D.C., tavern. Anna's facial features in this illustration are shadowy, yet her dark, tightly curled hair and the contrast of her skin against the simple white cotton muslin dress make her racial identity unmistakable (Fig. 1). Her anguished leap put Anna's picture and story in one of the earliest anti-slavery writings of the new United States. Indirectly, she launched court cases, started the American Colonization Society, inspired congressional speeches, permitted her tavern-prison to burn to the ground, and put her jailer out of business. Anyone who saw the awkward yet arresting illustration of the falling woman could not forget Anna—or what she represented. But all Anna understood when she scrambled over the garret window ledge was simply that she "did not want to go."

Technically, nearly everything in the illustration/engraving is wrong, which is precisely why the image of the woman floating in midair is so disquieting.

Technically, nearly everything in the illustration/engraving is wrong, which is precisely why the image of the woman floating in midair is so disquieting. Her figure—larger than any window of the closest building—appears to have come from nowhere, as though she has been dropped from the sky like a crash-test dummy. The caption informs viewers that she "jump'd out of the window," yet Anna's position is discordant and disconcerting, given what is known about human bodies in freefall. In this century, one might accuse the artist of having Photoshopped a posed figure onto an existing street image. Her arms hang to her side; she is not flinging herself out into space, embracing death with arms wide open. She is not tumbling with clothing flying. Instead, her legs are drawn up demurely, as though she is sitting in a chair with skirts arranged modestly around her ankles, ready to serve tea.

Perhaps the illustrator did not understand the obvious physics of a human body falling. Or perhaps he intended to convey the woman's resignation: she wanted to die because life was simply not worth living anymore. Similar images of people hurling themselves from tall buildings have appeared in books and on the front pages of newspapers and magazines: the workers in Manhattan's Twin Towers, leaping from the iconic skyscrapers—hand-in-hand, neckties and skirts flying—having decided that death by falling was preferable to death by fire; the young garment workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911, who jumped from the windows as their ten-story Greenwich Village factory became an inferno. However, unlike the "jumpers" from the Twin Towers and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, Anna is alone. She has not been joined by others wishing to avoid a worse death. Her absolute solitude makes her situation all the more poignant.

The residential street below Anna is likewise empty, lifeless, even soundless. What is absent in the picture is as important as what is present. No one stands in the street as a witness to her fall. The windows and doors of the inexpertly drafted Federalist-style homes are dark and shuttered, revealing nothing of what is inside. The homes and even cobblestones are precise and orderly yet desolate, as though everyone is indifferent to the unfolding tragedy. The artist has included no details of furnishings or silhouettes of inhabitants peering out of windows. On the street, no servants or delivery workers are getting started with their day. No one has stepped outside to check the weather or sweep the doorstep. No birds are flying, no dogs are barking, and no cats return from nocturnal prowls. The window in the top garret, presumably her escape route, is open, but all other doors and windows are shut tight. The entire world is turning its back on Anna's plight.

Washington, D.C., historian Wilhelmus B. Bryan wrote in 1905 that the illustration of Anna's fall is "the earliest representation of a building in this city other than one erected by the government," yet the incongruities and odd perspective create an unsettling—rather than representational—depiction of Miller's Tavern and its F Street neighborhood.

Washington, D.C., historian Wilhelmus B. Bryan wrote in 1905 that the illustration of Anna's fall is "the earliest representation of a building in this city other than one erected by the government," yet the incongruities and odd perspective create an unsettling—rather than representational—depiction of Miller's Tavern and its F Street neighborhood.1 The silhouetted signboard is visible on the tavern and the adjacent walkway, distinguishing it as a business on a street of homes. Anna herself casts a blurry shadow on the building facade. Two spindly trees stand like pillars between buildings at the end of the block. The square is cobbled and tidy but devoid of any living thing. Above her we see the empty sky with a few impassive dark clouds. Although the narrative explains that Anna jumped from her window at daybreak, the illustration depicts a moment without time, an event happening in slow motion. Even the shadows are wrong: sunlight on the building faces belongs with mid-day. The lighting on the trees is correct, but it is coming from the wrong side of the street. The multiple vanishing points are in the vicinity of the trees, but they do not line up on a common horizon. This geometric impossibility reveals the artist's inexperience to a knowledgeable viewer, but at the same time, the awkward arrangement of buildings and streets gives the image an otherworldly subliminal twist. Consequently, the illustration requires the suspension of disbelief in much the same way that an audience attends a play. The image is an enigma, and viewers want to know more. As a solo performer in her own drama, Anna's act demands that viewers participate in her tragedy.

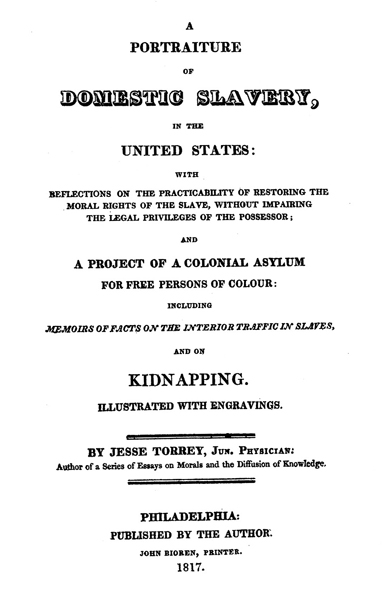

Anna survived her fall long enough to explain her actions to Jesse Torrey, a young Pennsylvania doctor on a tour of the new capital. As he prepared to attend a session of Congress, Torrey had already been shocked by the ugly irony of slow and sorrowful slave coffle processions in full view of the new republic's proudest structures. Having experienced this road-to-Damascus epiphany, Torrey canceled his Congressional visit and determined instead to create a "faithful copy of the impressions…which involuntarily pervaded my full heart and agitated my mind."2 When he heard that a desperate enslaved woman had jumped from a window and then learned that she was badly (perhaps fatally) injured but still alive, Torrey rushed to meet with her to hear first-hand "what was the cause of her frantic act."3 Her story is the first of several accounts of Torrey's interviews with enslaved persons, slaveholders, slave traders, and kidnapped free African-Americans. In A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, a slim, 84-page leather-bound volume, Anna's is the second of seven engravings which faithfully—albeit not altogether skillfully—depict the stories resulting from Torrey's conscientious interviewing (Fig. 2). In examining the book in Standford University's Special Collections, Curator of Rare Books John E. Mustain confirmed that Torrey had enlisted the services of Philadelphia printer John Bioren to produce a self-published volume. When Torrey's book appeared—a little more than one year after Anna hurled herself from a third story window—it launched one of the first public discussions of the capital's active participation in that "peculiar institution."

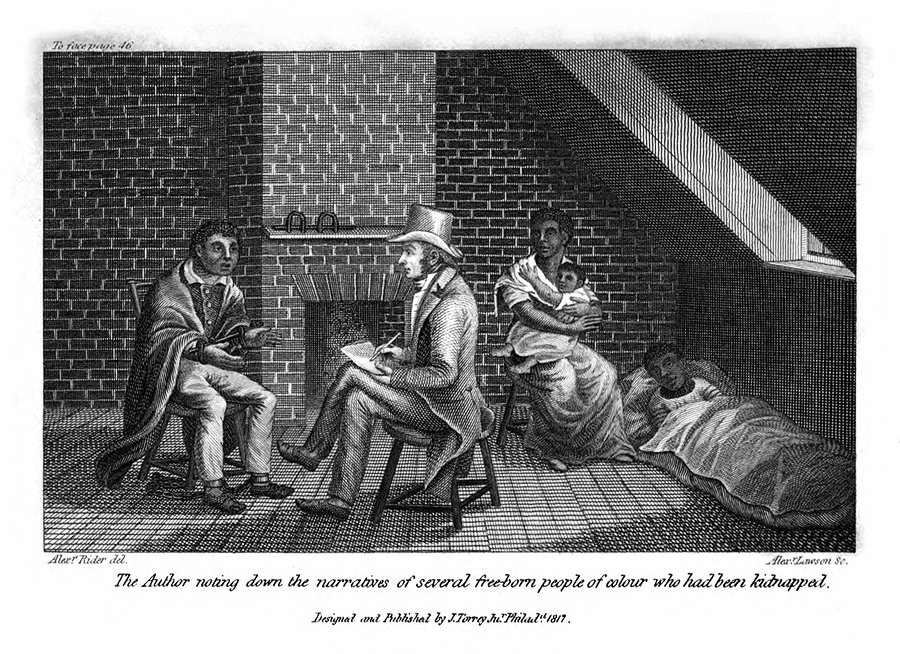

Little is known about Alexander Rider, the illustrator or "delineator" (indicated by "del." by his name) of all the book's images. Philadelphia's Biographical Dictionary of Lithographers notes that Rider was an artist's assistant from Germany or Switzerland who arrived in Philadelphia prior to 1808. By the time Torrey published his book, Rider was producing artwork on commission.4 In examining the illustrations in Torrey's book in Special Collections, Mustain speculated that notations on some of the book's illustrations (see name of engraver on right under Fig. 3) indicate that multiple craftsmen (with varying skill levels) completed the actual engravings. The printer tipped the artwork into the book following the artist's careful instructions for placement at the top of each picture. Captions under the engravings refer to quotations in the book. The high degree of consistency between the written narrative and the images is a matter of some conjecture. Torrey may have required Rider to include specific details in the illustrations; indeed, the credit line under each illustration states, "Designed and Published by J. Torrey," indicating that Torrey's control over the illustrations was exacting and precise. As a self-employed artist-for-hire, Rider himself might have been eager to earn a reputation as a cooperative illustrator by developing images mirroring textual descriptions. It is also possible that Rider refined sketches already provided by Torrey. A final explanation would be that the two men developed the finished illustrations in a mutually satisfying enterprise.

"They brought me away with two of my children, and wouldn't let me see my husband—they didn't sell my husband, and I didn't want to go. I was so confused and 'istracted that I didn't know hardly what I was about—but I didn't want to go, and I jumped out of the window...they have carried my children with 'em to Carolina."

Neither Torrey nor Rider, however, witnessed Anna jumping to the street in front of the tavern. The illustration is based on details Torrey noted of the tavern structure—a "three-story brick tavern in F Street"—when he interviewed Anna in the same room from which she had jumped days before.5 She was lucid but bedridden, with two badly broken arms and a "shattered" spine. Torrey learned that Anna "did not want to go" for a reason that echoes through slave narratives and American literature even today: the domestic slave trade and the dissolution of the families of enslaved people. Anna was one of thousands of American slaves—perhaps, historian Sven Beckert estimates, even more than a million—who were forcibly separated from their families to be sold "down the river" as the new republic stretched its borders to the south and the west.6 The narrative accompanying the illustration quotes Anna directly: "They brought me away with two of my children, and wouldn't let me see my husband—they didn't sell my husband, and I didn't want to go. I was so confused and 'istracted that I didn't know hardly what I was about—but I didn't want to go, and I jumped out of the window...they have carried my children with 'em to Carolina." Torrey comments, "Thus her family was dispersed from north to south, and herself nearly torn in pieces, without the shadow of a hope of ever seeing or hearing from her children again."7 The sorrow of losing spouses and children would continue as a common refrain in memoirs, narratives, and novels that touched on the American slave trade.8

Anna appears again in another illustration in the book which reveals how she unintentionally led Torrey to uncover an even darker practice within the walls of Miller's Tavern and in Washington's slave trade. When Torrey interviewed Anna, he met three more prisoners being held in the same room. The image of his next conversation, which appears several pages later, shows Torrey interviewing these cellmates as Anna lies under the dormer (Fig. 3). As before, Rider's stippled illustration includes precise details from the text: the room is in a "brick" tavern; Anna's blanket is "white woolen." One of the companions is a 21-year-old "mulatto" man who is "thoroughly secured in irons...with strong loops round his wrists...connected by a strong iron bolt. On the shelf, over the fireplace, lay a pair of heavy rough hopples [hobbles] with which he said his legs had been fettered...but were then secured by a pair of polished gripes [grips]...connected by a new tug chain." The other two people in the room are a "widow woman with an infant at her breast" (unrelated to the mulatto man) who had been "seized and dragged" out of bed in her home. A subsequent illustration depicts the woman's kidnapping. Torrey is outraged to learn that—unlike Anna, who was a "legal" slave—the man, woman, and child are all free-born citizens taken from their Delaware homes by "man stealers."9 As Torrey discovered, slave traders and jailers in Washington, D.C., were not particular about the status of the men, women, and children in captivity. Regardless of status, any person of color was vulnerable.

When Anna's plight became known, Torrey gained an unlikely ally in John Randolph, a slave owner himself, who realized that the image of a desperate woman jumping out of a building made a mockery of his earlier public claims that slave holders were benevolent. The congressman tried in vain to convince colleagues to honor the "federal" nature of the District of Columbia by banning the slave trade within the capital's jurisdiction.10 Although unsuccessful in that effort, Randolph joined Torrey as one of the earliest proponents of what eventually became the American Colonization Society. As historian Nicholas Wood explains in his biographical study of the congressman, Torrey's book—and Anna's act in particular—exposed the depravity of the slave trade in the capital city in ways that even a slavery apologist like Randolph could not ignore.11 When Anna jumped from the window, she turned the slave pens and slave taverns inside out: the illustration ensured that no one could look away.

Anna's ultimate fate continued as a topic of local gossip and speculation, yet despite conflicting opinions, Torrey's book and the unsettling illustration of her jumping from the garret window secured her place in neighborhood lore. Thus, over two years after the publication of A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, historian Wilhelmus B. Bryan describes how Anna returned to public awareness when a fire engulfed the stables and outbuildings of Miller's Tavern. As the tavern burned, nearby residents obliged to serve in local fire brigades arrived with buckets to douse the blaze; as they assembled, they talked about Anna and other involuntary "guests" held at the tavern. Some of the neighbors reported that Anna had died shortly after Torrey had interviewed her. Others said that the tavern still served as a depot for enslaved people about to be transported elsewhere. Many, like post office clerk William Gardner, announced loudly that they would do nothing to help the "Slave Bastile." They turned their attention to nearby properties and allowed the tavern to burn to the ground.12

Anna never knew what she started when she jumped out the window and survived to talk about it. She likewise did not know that many of us view the haunting image of her "frantic act" as the embodiment of the systematic destruction of enslaved families, a practice that would continue for another fifty years. Because the illustration and its accompanying narrative tap into the timeless and universal sorrow of forced separation, we find ourselves with Anna at the garret window. We imagine her anguish as everything and everyone are ripped away from her. We share the despair of a wife and mother who will not ever know what happened to her family. We open the window and feel the cold dawn air on our face, knowing that soon we are to be chained to the rest of the coffle for the long forced march south. We look at Anna's future through her eyes: a bleak chasm, filled only with endless days of unrelenting toil, abuse, and misery. We gaze down with her on the empty, cobblestoned street below. The world is motionless, silent, and indifferent. And like her, we don't want to go.

Endnotes

1. Wilhelmus B. Bryan, "A Fire in an Old Time F Street Tavern and What It Revealed," Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. Vol. 9 (1906), 200. [back]

2. Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, in the United States (Philadelphia: John Bioren, Printer, 1817), 40. [back]

3. Ibid., 46. [back]

4. Rider, Alexander, Philadelphia on Stone Biographical Dictionary, Library Company of Philadelphia. Rider's later work holds some value today: in 2014, art auctioneer Graham Arader offered a single watercolor by Rider with an auction price of $175,000. Interestingly, the gallery's details of the plate remark that Rider"s work is an "[instance] of the collaboration between author and artist." As this description is consistent with Rider's illustrations for Torrey, it is possible to speculate that he was an especially collaborative artist. [back]

5. Art historian John Davis's research places the tavern's location across the street from the "yard" depicted a half century later in Eastman Johnson's Negro Life at the South. Davis contends that in the 1850s, the immediate neighborhood of F Street (near 13th and 14th Streets) was unabashedly pro-southern (Johnson's own family being a possible exception). John Davis, "Eastman Johnson's Negro Life at the South and Urban Slavery in Washington, D.C.," Art Bulletin (College Art Association) 80.1 (March 1998), 76-77. [back]

6. Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 109. [back]

7. Torrey, 46-47. [back]

8. In autobiographical writing about his riverboat days, Mark Twain—who appropriated the family separation trope in Huckleberry Finn in describing Jim's efforts to win freedom for himself and his family—wrote: "I vividly remember seeing a dozen black men and women chained to one another...awaiting shipment to the Southern slave market. Those were the saddest faces I have ever seen." Mark Twain, The Annotated Huckleberry Finn, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn. 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2001), 93. [back]

9. Torrey, 41-43, 46, 48. With the help of "Star Spangled Banner" lyricist (and attorney) Francis Scott Key, Torrey was able to get a court injunction to forestall the enslavement of the man and the woman and her infant who were being held with Anna. They were all subsequently returned to their free status in Delaware. Jesse J. Holland, Black Men Built the Capitol: Discovering African-American History in and Around Washington, D.C. (Guilford, CT.: Globe Pequot Press, 2007), 83. [back]

10. Despite Randolph's efforts, the slave trade and the kidnapping of free African-Americans continued in Washington, D.C. Perhaps the most well-publicized incident occurred over twenty years later when Solomon Northup, who wrote of his enslavement in Twelve Years a Slave, was kidnapped and held in Washington, D.C., in 1841. He was transported from there to Louisiana. Northup was successful in regaining his freedom, but hundreds if not thousands of other free African-Americans were not as fortunate. Because of its geographic location and the large number of free African-Americans in Washington, D.C., and nearby mid-Atlantic states, the capital city was a common site for what Torrey referred to as "man-stealing." Mary Beth Corrigan, "Imaginary Cruelties? A History of the Slave Trade in Washington D.C." Washington History Vol. 13, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2001/2002), 10-11. [back]

11. Nicholas Wood, "John Randolph of Roanoke and the Politics of Slavery in the Early Republic," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 120.2 (Summer 2012), 119. [back]

12. Bryan, 198-201. In the aftermath of neighbors' refusal to help with the fire at Miller's Tavern, an exchange of letters between William Gardner and tavern owner George Miller appeared in the City of Washington Gazette on April 29 and May 11, 1819 (respectively). The letters offer alternate versions of Anna's fate. Gardner writes that neighbors told him that Anna had died of her wounds. Miller answers that Anna survived as a consequence of "humane care and attention" from his family. He adds that he "purchased her, and she is now in my service." Miller did not prosper after the fire. Articles in Washington, D.C., newspapers from 1819 on carry frequent notices of property seizures for payment of his debts and back taxes. By 1824, a front page National Intelligencer notice announces that a new owner has restored and re-named the tavern as Lafayette House; nevertheless, the building continued as a place for holding slaves (Holland, 28). An article in the May 30, 1829 issue of the National Intelligencer identifies Miller as one of three individuals indicted by the Grand Jury of Savannah for false imprisonment of Rowland Stephenson (3). Stephenson was, interestingly, not enslaved nor was he even an American. He was a slippery English banker on the lam whom Miller and a fellow slave trader William Williams (the owner of the infamous "Yellow House" slave prison) abducted in hopes of receiving reward money for his return to angry investors. Miller and Williams both pled guilty and were fined and imprisoned for six and three months respectively. [back]