The Business of a Nascent Federal Court: Records of the Circuit Court for Washington, D.C. from 1801-1802

James Sterling Young's award winning study—The Washington Community: 1800-1828 (1966)—recreates Washington society as it emerged in the Early Republic.1 While it deftly explores the relationship between the executive and Capitol Hill, it just as glaringly neglects the judicial bureaucracy of the new capital. In fact, the index only refers to the courts under the heading "Supreme Court" and references the Court on a meager six pages.2 This scant treatment reflects the numerical diminutiveness of federal law enforcement. In 1802, federal law enforcement consisted of one attorney general, thirty-six district judges, twenty-four district attorneys, twenty-four marshals, and eighteen clerks—only 1.1 percent of the federal bureaucracy.3

Indeed, historical studies of antebellum court business are just as sparse. Felix Frankfurter's pioneering 1920s study of the business of the Supreme Court focuses virtually all of its attention on the period after the Civil War. That Congress did not require regular reports on judicial business until the 1870s contributes to this scarcity of inferior court studies. Frankfurter lamented "the volume of this appellate business compared with their original jurisdiction is not disclosed by available data."4 Frankfurter's assertion that court business could not "be accurately estimated until the dockets of the federal district courts are studied" underscores the need for and importance of the O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family project.5

This paper begins the long (and much needed) process of reconstructing the judicial business of the D.C. Court by exploring the minutes during the Court's first three sessions in Washington, D.C., from 1801-1802.

The OSCYS project is in the process of digitizing records of the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia during the antebellum period. Beyond providing open access to petitions, records, case files, etc., the Court's minute books may also be transcribed. The minutes are the essence of the day-to-day business of the Court and provide insights that published case reports cannot. This paper begins the long (and much needed) process of reconstructing the judicial business of the D.C. Court by exploring the minutes during the Court's first three sessions in Washington, D.C., from 1801-1802. Far from the contention "Early in its existence, the District of Columbia Circuit Court had little work and there was talk of abolishing it," the newly created federal inferior court adjudicated an ample and diverse docket.6 The Court's activities supported economic growth and the enforcement bureaucracy. However, rather than "[taking] the lead to in developing new law to meet the demands of a growing economy and a changing society"—as legal historians have concluded about lower federal courts in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—the D.C. Court served a far less glamorous, more bureaucratic and administrative function.7

The Court's activities supported economic growth and the enforcement bureaucracy.

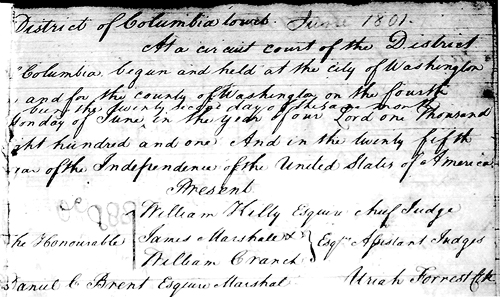

Congress created the District of Columbia Court on February 27, 1801.8 "An Act Concerning the District of Columbia" split the district into two counties—Washington County and Alexandria—and established a court to oversee the new capital. The Court consisted of one chief judge and two assistant judges and was to meet in each county four times per year. Along with appellate jurisdiction, the Court claimed original jurisdiction in all civil and criminal causes within the district. When legal actions involved citizens from Maryland, Maryland law governed the outcome. The same held true for Virginia. Thus, the Court's original jurisdiction in criminal and civil causes within the district provide the basis for this study. Unfortunately, the minutes for the Court's Alexandria sessions have not been analyzed because they are housed with the Alexandria records—a split that occurred in 1846.9 The data for this paper is taken from M1021, Minutes of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, 1801–1863.

In its first year in existence, the District of Columbia Circuit Court met for the first time on June 22, 1801. Thomas Kilty sat as the Court's first chief judge; William Cranch and James Marshall served as assistant judges. The Court administered a diverse docket. The judges presided over criminal trials and equity suits. They granted local licenses and naturalized citizens. They swore in witness, grand juries, and attorneys as well as appointed marshals, clerks, and constables. In its first three sessions, the Court handled no less than 216 causes/licenses. Here is the breakdown of causes by session:

- Session 1, June 22, 1801 – July 10: 106

- Session 2, September 28 – October 8: 55

- Session 3, December 28 – January 9, 1802: 55

Session 1, June 22 – July 10, 1801

Pages one through twenty-seven of the minute books contain the records of the first session of the Court. It appears—although it is sometimes difficult to distinguish—the Court ruled on no less than 106 causes/licenses during the session. However, the Court only met for two full weeks before taking a week-and-a-half break for the Fourth of July Holiday and then returned to conclude its business on July 10. The majority of the Court's work appears to be administrative. It began the session by swearing in the grand jurors, witnesses, and attorneys who appeared before it. Additional grand jurors and witness were also sworn in sporadically throughout the session. Only two probate decisions exist, and one of those is for legal guardianship.

Two additional administrative tasks were naturalizing citizens and appointing overseers of roads. On July 10, Thadey Hoagan of Ireland and Hugh Densley of England swore their naturalization oaths. On July 1, Richard Jameson and Abraham Boyd received separate appointments to oversee one of the District's roads.

By far, most of the administrative duties consisted of issuing licenses. It is difficult in many cases to distinguish between a license and a fine, but it appears approximately ninety licenses were issued during the first session. Interestingly, at least half of those were for retailing liquor. Alcohol appeared to be in high demand—or at least very readily available—in the nation's capital. The clerk labeled liquor as either "punctiuos," "spirituous," or "ordinary." In only a few cases were dollar amounts attached for these licenses. George Jacobis and John Kearney each paid "$53 1/3" for their licenses, while Pontius D'Stille paid $100. James More purchased two different licenses—one for $100, and one for "$53 1/3." Clearly, the most urgent business of this sparsely populated swamp was keeping the liquor flowing.

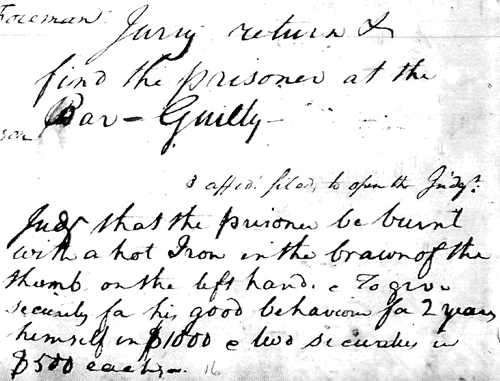

The Court conducted at least nine criminal trials during the first session. Information on the trials is limited, but four were for stealing, and another charged assault and battery. It is unclear—beyond felony charges—what the specific offenses of the remaining four defendants were. What is intriguing is the severity of the punishments. The Jury found Samuel Baker guilty, and he was sentenced "to be burnt with a hot iron in the brawn of the thumb on the left hand."10 The Court sentenced John Clancey to be publicly whipped and another guilty party "to be pillar for ¼ an hour."11 For stealing a hand chisel, Charles Houseman received "20 strikes."12 It appears citizens deemed stealing a larger threat than assault, based on the punishments doled out. For example, for his conviction of assault and battery, John Cannon was fined $15 and avoided physical retribution.13

It appears citizens deemed stealing a larger threat than assault, based on the punishments doled out.

Session 2, September 28 – October 8, 1801

Court business slowed in its second session. The total number of causes/licenses decreased to no fewer than fifty-five. Moreover, the Court conducted only three trials during the two-week period it operated. Of note, the sentence of Daniel Henderson for stealing silver candlesticks specified he receive 30 strikes on his "bare back" and an additional fine.14 It is unclear whether previous convictions resulting in "strikes" were "bare back" or clothed.

Perhaps more important for the growth of the new capital, the Court naturalized 14 individuals and granted a license to operate a ferry after spelling out the application terms. On October 2, the Court directed license applicants to publicly announce their intentions:

The Court will not act upon any Petition for license to Open a new Ferry unless the petitioner shall have given public notice by advertisement inserted in some public Newspaper or Newspapers published within this District 3 weeks before the sitting of the Court of his intention of applying to this Court for such license.15The Court subsequently granted its first ferry license on Tuesday, October 6.16 The minutes make no mention if the applicant fulfilled the Court's requirement prior to its announcement of the official procedure.

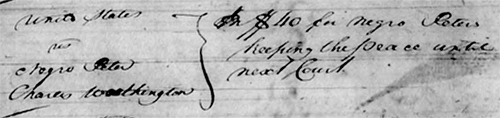

Two additional interesting anecdotes are worth mentioning. The minute books distinguish race for the first time on page 42. A man by the name of what appears to be Peter is referred to twice as "Negro Peter." First, in the name of the cause and second, in the subsequent description: "$10 [or $110] for negro Peter keeping the peace until next court."17 Either there had been no causes involving African Americans prior to this one, or the minutes do not consistently distinguish between blacks and whites. This session is also the first time we see references to habeas corpus writs. There are two mentions of writs directing the court to produce prisoners.18

Session 3, December 28 – January 9, 1802

In the third session, the Court's docket appeared to gain some consistency. It dealt with no less than fifty-five causes/licenses. However, the number of trials increased to thirteen, and the first civil trials appear in the minutes. Daniel Carrick sued John Read, and the jury found in the plaintiff's favor in the amount of $50 and the jury fee.19 It is unclear who the parties were in the second case, but the result found one party owing $100 to the other.20

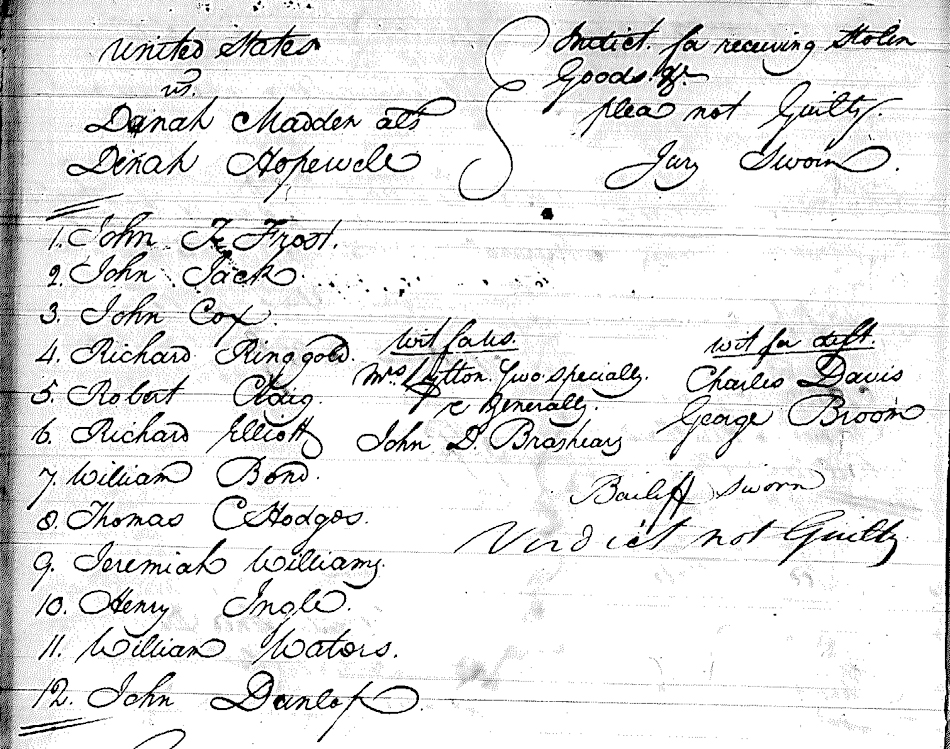

The Court continued facilitating the economic growth of the District. It granted multiple ferry licenses and dozens of retailing licenses. The trials were pretty strait forward, but significantly the Court tried Dinah Madden twice for receiving stolen goods, and each time the jury returned with "not guilty" verdicts.21

Rather than keeping the peace and administering justice, the minute books of the first three sessions of the District of Columbia Circuit Court evince a Court facilitating a new a growing economy. Granting business licenses consumed the Court's docket. It did not have much of an early role in settling civil disputes; however, its unique original jurisdiction in criminal cases demonstrates an acceptance of physical punishments for the theft of property while assault and battery convictions were met with fines.

This brief study opens the door on early Washington, D.C., as a growing economic enterprise, but the minute books need a further detailed exploration.

This brief study opens the door on early Washington, D.C., as a growing economic enterprise, but the minute books need a further detailed exploration—both the ones mined in this paper as well as the books of the Alexandria Court. The study could be expanded temporally to get a larger sample of the business of the Court in the antebellum period. Perhaps increments of five or ten years will offer a more precise picture of the Court's growth and influence.

In terms of social history and relationships, the names on jury roles, witness lists, and attorney lists could be mined to help develop the social circles of the new capital. The Early Washington D.C. Law & Family project should provide future scholars an opportunity to explore all of these avenues.

Endnotes

1. James Sterling Young, The Washington Community: 1800-1828 (New York: Harbinger, 1966). [back]

2. Ibid., 306. [back]

3. Ibid., 29. [back]

4. Felix Frankfurter and James M. Landis, "The Business of the Supreme Court of the United States. A Study in the Federal Judicial System," Harvard Law Review 38, no. 8 (June 1925), 1016. [back]

5. Ibid., 1016, note 35. [back]

6. Claim made in: "William Cranch" in "Guide to the Early Reports of the Supreme Court," 1 Guide Early Rep. Sup. Ct. U.S. 25 1995, 26. Accessed at HeinOnline. [back]

7. Melivin I. Urofsky and Paul Finkelman, A March of Liberty: A Constitutional History of the United States, Volume 1 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 183. [back]

8. "An Act Concerning the District of Columbia," February 27, 1801, 2 Stat. 103. [back]

9. National Archives and Records Administration, "The U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, 1801-1863." [back]

10. M1021, Minutes of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Columbia, 1801–1863, Roll 1, page 12. [back]

11. Ibid., 16. [back]

12. Ibid., 17. [back]

13. Ibid., 18. [back]

14. Ibid., 61. [back]

15. Ibid., 51. [back]

16. Ibid., 58. [back]

17. Ibid., 42. [back]

18. Ibid., 62-63. [back]

19. Ibid., 86. [back]

20. Ibid., 87. [back]

21. Ibid., 83, 89. [back]